In Amerika They Call Us Dykes: Redux

I’m going back to the archives. I find them more meaningful than ever.

If it hadn't been for feminism, there never would’ve been women making their own dirty pictures.

This is the irony of the feminist erotica/porn debate. Lesbian-made portraiture arose in the early 1970s as a renunciation of the commercial porn boys club, a slap in the face to heterosexism and the male gaze. It was, and is, a tribute to authenticity in the women's community.

Women are tough, and the feminist style is even tougher. From the beginning, lesbian sexual expression was a tribal stomp, filled with volunteers in the Amazon Love Army— dedicated to sexual freedom, and smashing the closet. It was the inevitable synthesis of women's liberation and gay power.

Some leaders in the establishment women's movement — cough cough — didn't appreciate sexual frankness. They said it was exploitative, male-identified, or just plain indecent. I actually took their complaints seriously at the time, engaged in endless earnest debates.

Then I saw my opponents’ bookshelves. Their underwear drawer. I overheard their confidences, and they were as sex-preoccupied as anyone else. They didn’t have cogent arguments, they had turf, and they’d say anything to keep it.

Not the first or last time sisterhood got reduced to crabs in a bucket.

It didn't change the fact that erotic demonstration was indeed the work of their sisters. Lesbian self-representation is the perennial gauntlet thrown down in the face of passive feminine objectification, and nothing has been the same since.

In 1973, a book called Our Bodies, Ourselves arrived on the scene, representing the flower of activist feminism. It was a radical feminist manifesto, covering reproductive rights, sex, childbirth, menopause— and practical tools to take medical power into your own hands. How I remember buying my first speculum and taking a look at my cervix!

Our Bodies, Ourselves’ grassroots movement literally changed the global map for women's healthcare— and one of its most influential sections was not about medicine at all. The chapter was called, "In Amerika They Call Us Dykes,"1 written by the Boston Gay Collective. This militant treatise defined the possibilities of living as a blatant lesbian, in a feminist world where egalitarian and women-first principles ruled.

It is no longer in the current edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves. The chapter on lesbians is now titled: "Loving Women: Lesbian Life and Relationships," and let’s just say, it’s not as riveting!

"In Amerika They Call Us Dykes" featured photographs of real lesbians like Doreen Querido,2 looking happy as a clam, full-face to the camera, jaunty in her hat and trousers. It was the first identified photograph of a contemporary lesbian that most women had ever seen.

The chapter and those photographs prompted hundreds of women to write to the Boston Women's Health Collective, basically asking, "Where can I meet women like this?"

I’m going to Ithaca this week to work on the On Our Backs archives at Cornell Library’s Human Sexuality Collection.

I’ll be on campus for the spring quarter— and I’ll let you know when I hold a couple public events. I love to introduce people to the archive.

My ongoing mission is to describe every donated item of our archive onto paper, spreadsheet, or video. I want our names, dates, and stories on the record, and I have to get these details out of my head before I lose anymore of my marbles!

I can’t tell you how frustrating it is to open a historical box of letters and photos in a precious archive only to discover there are no names, no dates, the barest of clues.

I will leave a clue. We changed things. Some of us are still alive. People are going to know about it.

The Boston collective was quite audacious to devote such an important part of its book to lesbianism. Most feminist publications at the time were wary of the consequences of associating anti-sexist ideas with dykehood, even if their own members were exploring the connection. Some feminist organizations, like the National Organization for Women (NOW), had bitter fights about the visibility of lesbians and lesbian rights.

But the argument to be, or not to be, out of the closet was a bit beside the point— lesbians were already the foot soldiers. Lesbians had been involved in the trenches of civil rights movement in the 60s; the cadre of the reproductive rights movement. Lesbians were the ones to break away from the male left, and from trad romance, to invent their own communities, land projects, and female-only communes.

It was more extreme than getting the post office to address you as "Ms."— it was a whole new way of communicating.

The feminist radical body aesthetic was initially a “Fuck That” reaction. A rejection of Playboy magazine. Feminists felt universal distress about the cheesecake formula of femininity, which amounted to treating women like they were cocker spaniels in a Dog Fancy magazine.

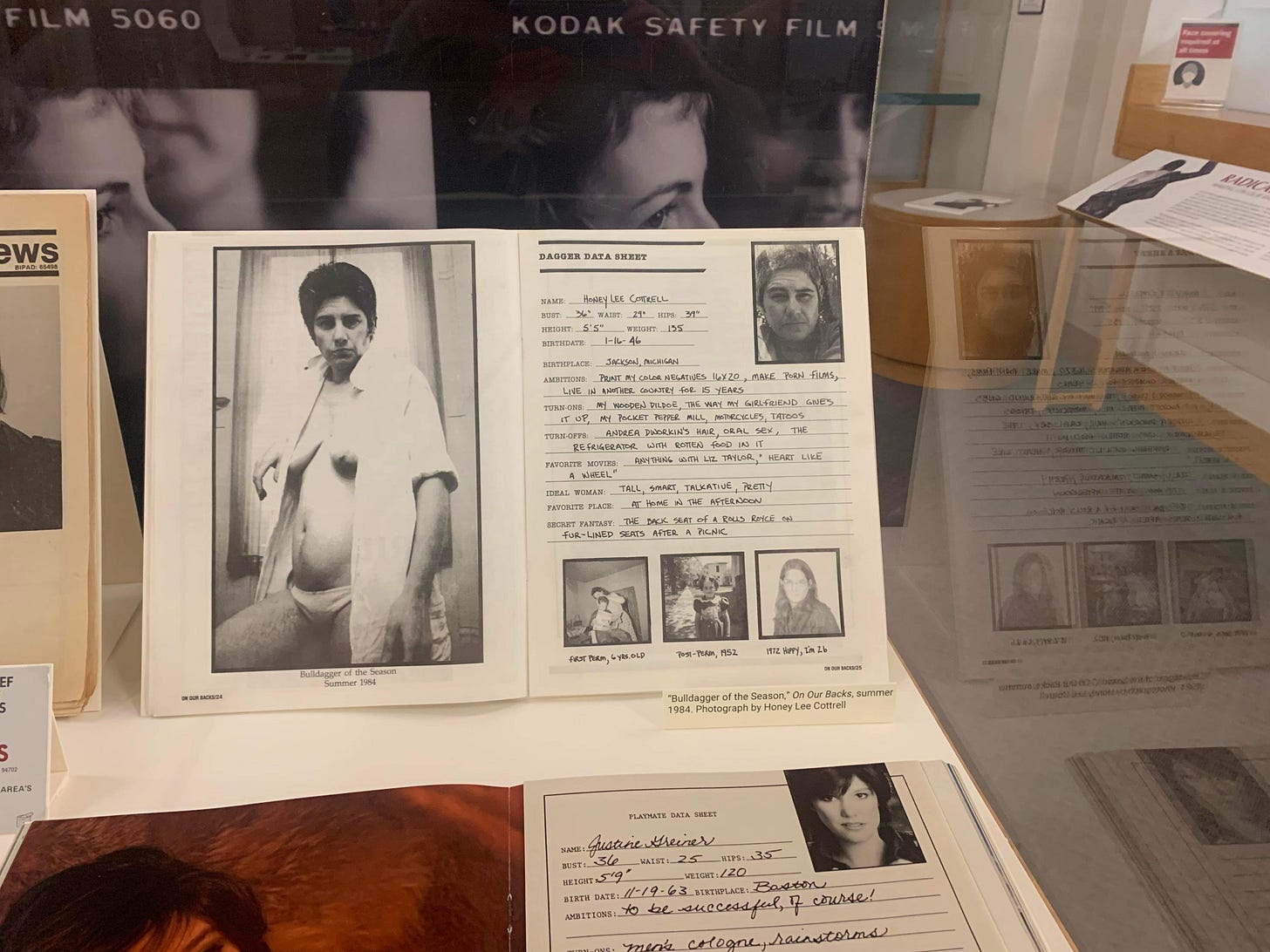

In the first issue of On Our Backs, the staff decided to run a Playboy centerfold parody called "Bulldagger of the Season," a self-portrait by Honey Lee Cottrell. In the photograph, Honey Lee 's dark eyes burn holes right though Amerika's worst fears for their daughters. Across the page from her adult dyke portrait, we printed her turn-on's and turn-off's, as well as the standard darling childhood photos underneath her answers.

Oh boy, it was fun. We got furious letters from feminists saying it was sexist. We got furious letters from lesbians saying it was atrocious to feature a butch, they said we needed to look at a few Penthouse Pets for tips. And we got delirious letters from gals asking for Honey Lee’s phone number.

My favorite letter was the young woman who said, “I just took my first women’s studies class and I’m not sure what I’m supposed to think. What if the woman in the picture is a bad person?”

Vogue, Playboy, and Dog Fancy have never had this kind of debate!

Of course there were no "should's" about it. Honey Lee's portrait was deliberately dark, and the layout was pure satire. But her intentions were lost on many members of a women’s community just emerging from complete erotic silence.

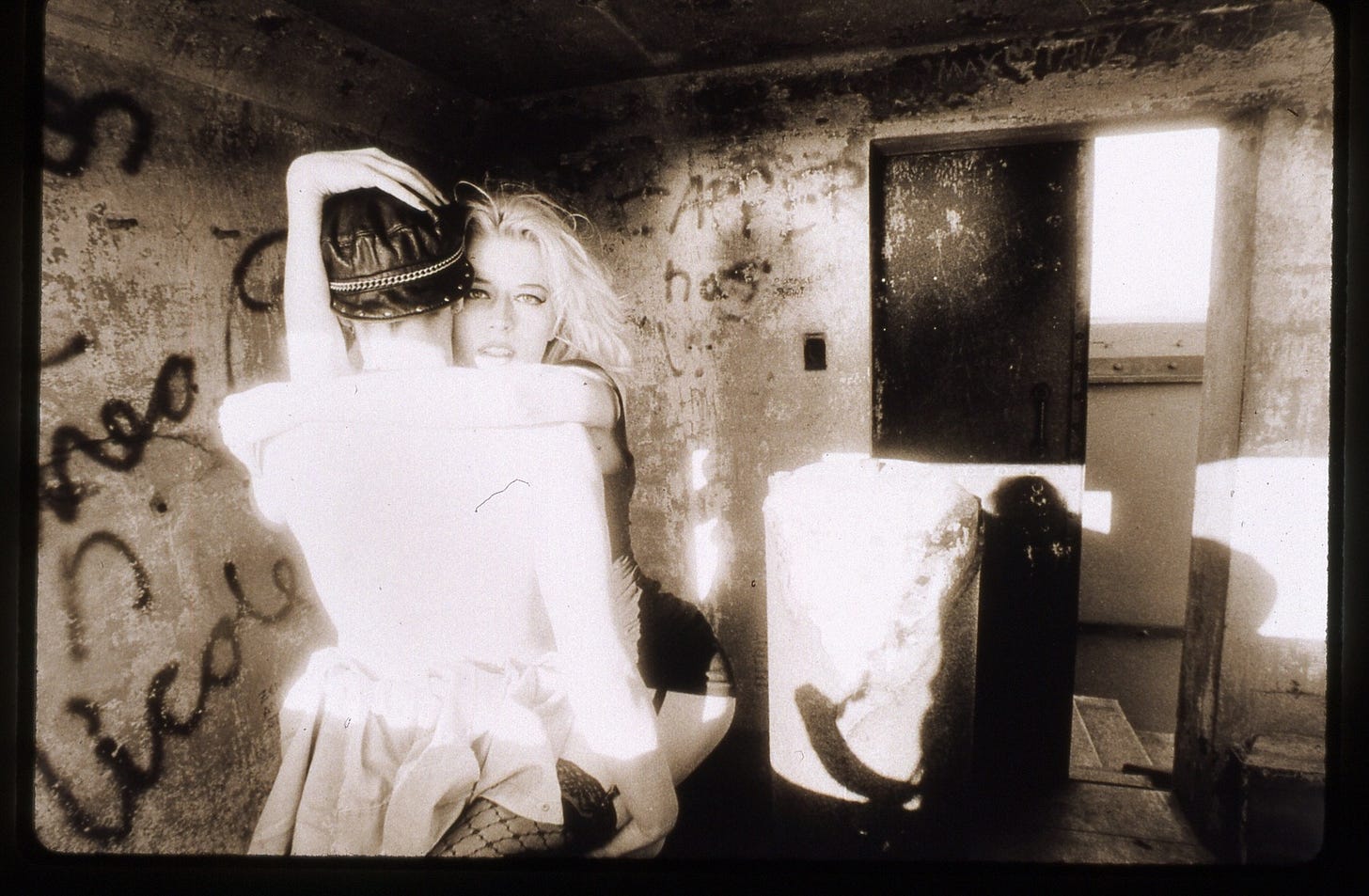

And the straight world? Well, bohemians of all stripes embraced us. We were joined politically.

But yes, I met with a lot of shock, wherever I traveled. Ours was a world where women were not concerned with “preserving their virtue.” Where such a phrase had no meaning. Where we lit a spark without apology.

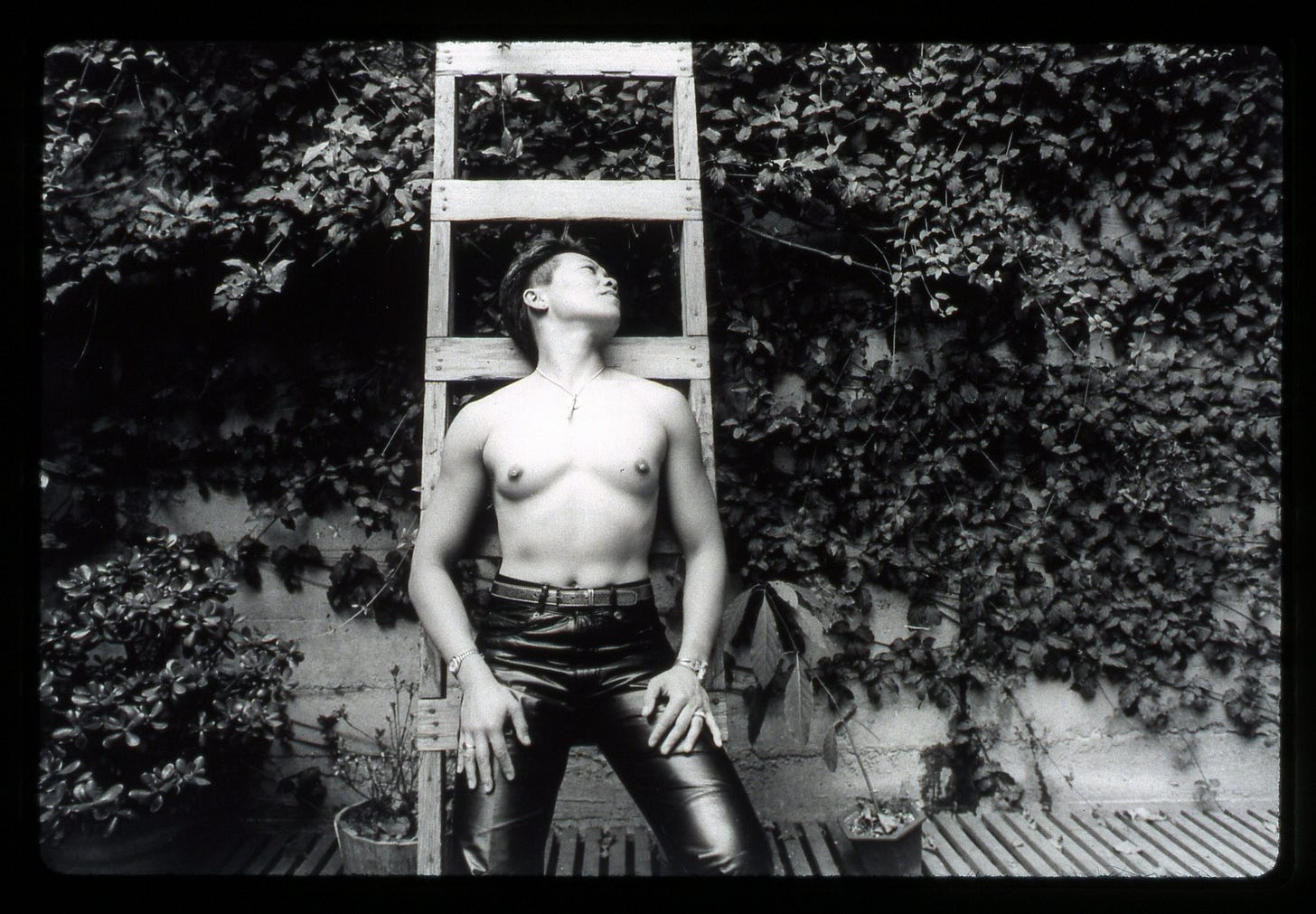

Erotic portraits that exemplify egalitarianism, diversity, and authenticity are the ones that create the most internal dissension. Remember, there were no erotic self-made pictures of any lesbians to look at until the mid-1970s. Young, white, middle-class women, who felt they had the least to lose and the most impetus to piss off their parents, were the prime candidates for lesbian modeling— they still are, actually.

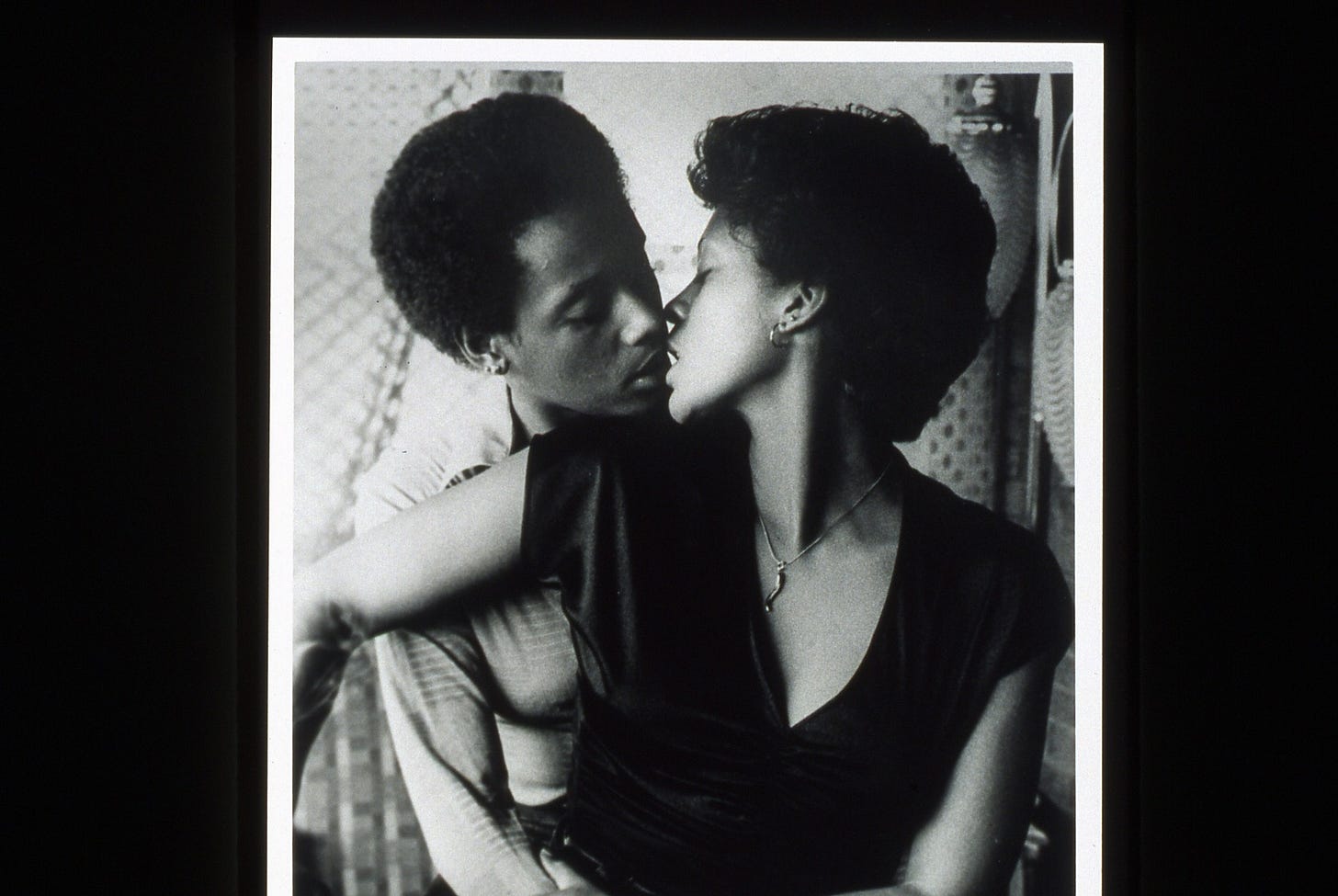

Photographers who deliberately sought out portraits of Black, Asian, and Latina women, or working-class women, were documenting a gay style and face that was literally unseen in the mainstream women's movement (let alone anyplace else); and this distinguished On Our Backs as much as the erotic content.

One would think that this kind of portrait would be applauded by the feminist status quo. It was . . . but only if those faces and models were an ethnic version of the "Union Maid": heroic, noble, not too butch or femme, and certainly not sexually confrontational. Like a Benetton ad.

This criticism came down from the nay-sayers as feminist rhetoric but it was really just plain prejudice and snobbery. Who are these street kids?

I can't even begin to count all the photographers from non-white backgrounds who told me that they could not endure the embarrassment and anger they imagined would result from publishing erotic photos of their community and background.

They weren’t just paranoid-- they could easily anticipate racist assumptions attributed to their sexuality (black bitch, black butch, geisha girl, dark girl as slut, etc.)— or accusations of exploitation and betrayal from their community and families.

The artists and models who pioneered erotic expression from non-white and/or working class circles were extraordinarily courageous: they were putting themselves on the line before anyone else had the nerve— confronting, with tremendous style and intimacy, the identity of a lesbian outside of a WASP-colored world.

Sexuality for the disabled was another topic pioneered by lesbian artists. Tee Corinne's' solarized photograph of lovers with a wheelchair transformed a cumbersome reality into the ultimate lesbian love vehicle.

When I published the lesbian erotic photography book “Nothing But the Girl” with Jill Posener, we wanted to have a reckoning and lesbian woman and disability, because we knew dykes were once again, at the forefront.

Gon Buurman's picture of a woman lying on her bed with her dildo raises more questions. This time we see a woman with a deformed forearm who appears to have enjoyed masturbating with a dildo, which itself has a unsuspected visual referral to her hand.

Gon was asked by her Netherlands government to profile a series of Dutch disabled citizens in their daily life, including their sexual lives, their private lives. (Americans:boggled).

I was attracted to the photo that shows Buurman’s model as sexual and orgasmic, but some viewers skip ahead to other potential messages. Does this photograph lead one to believe that the model is lonely? That her sex toy is her "only' alternative? Or is it straight-ahead pro-masturbation material? Is it exploitative, "freakish' to visualize sexuality with a handicap?