I Was a Little Canadian Girl - What Happened?

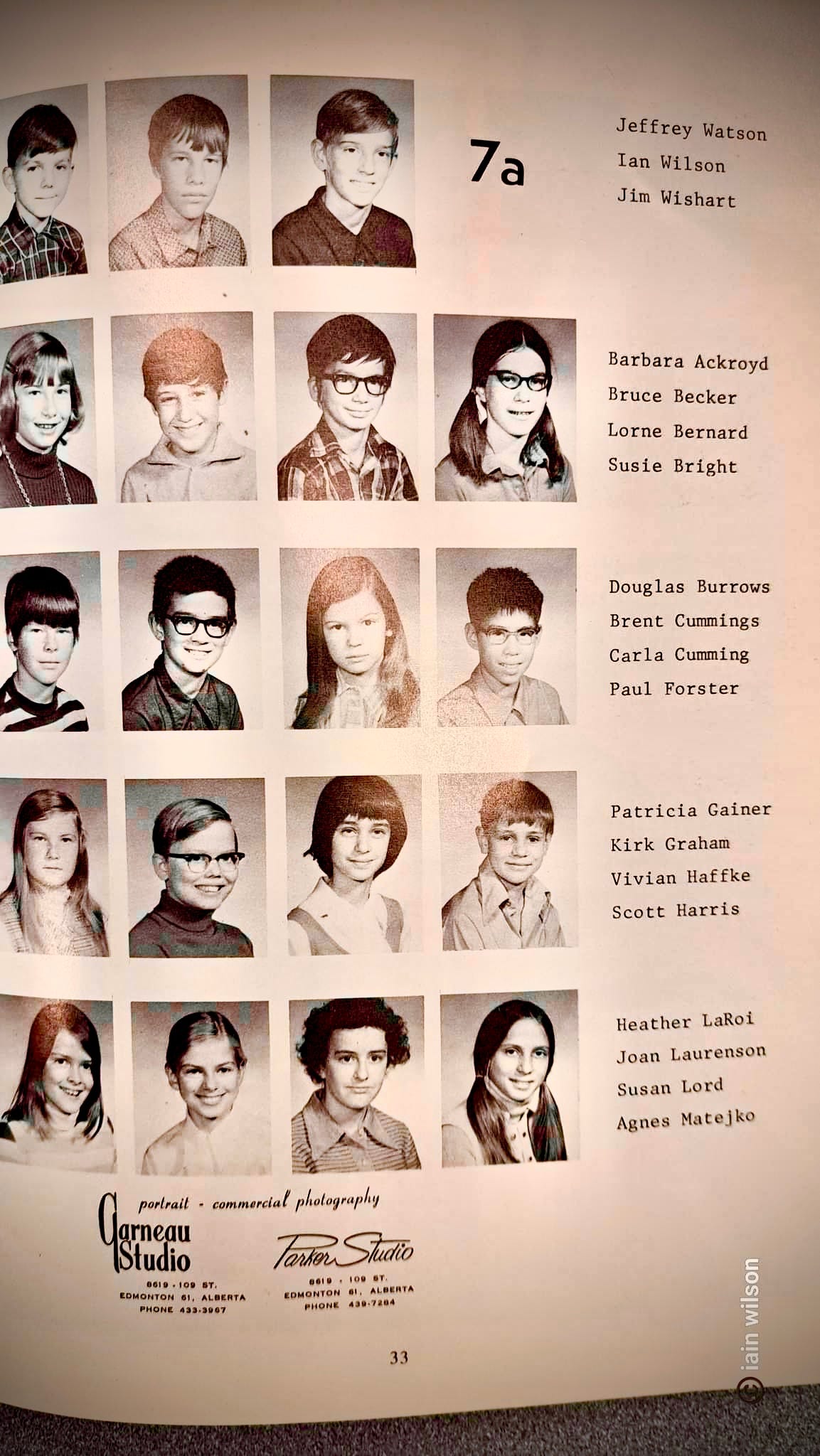

I have unearthed my puberty in Edmonton - when the world was changing, even at the highest latitudes

I WISH I had a hometown.

I always wanted a place I could look back and say, “I saw it all!”

No, I didn’t grow up in a military family. I grew up with a mom who thought the grass was greener on the other side. I went to 10 schools in 13 years. Even spending two grades in one place, made a tremendous impact on my social psyche.

One of those lucky spots was . . . Edmonton, Alberta. —My mother’s biggest leap of all.

And if your first thought is, “Where’s that?” — it was also mine. I had never heard of the place when we packed our bags and set out from Los Angeles in our 1963 VW Bug.