Falling in Love with “The Romantics”

I will remember Pankaj Mishra’s Indian memoir, in the quiet hours before New Year’s, the abyss edge of the Donroe Doctrine.

Last week I fell in love with Pankaj Mishra’s roman a clef, The Romantics. I’d like to share a little bit of it with you today — both reading from the first chapter, and explaining why a story based in 1980s on the River Ganges means so much to my private floating world in the 21st century.

The story, autobiographical to a sweet fault,1 is about a young man, Samar, who supposed to do his tedious duty in college, and save his Brahmin heritage from waste. Needless to say, he has his head in his Western books (Turgenev! Schopenhauer!) and has never, in his sheltered life, had five minutes of a normal social interaction.

—Enter the corrupting Europeans, the English and French! Ooo la la.

“I had never been to a party before,” he writes. I am sure this taken straight from the author’s diary.

There’s nothing like a party, and a first love, that will change your life.

Yes, this book is a romance, a comic-tragic one. I shouted more than once. I could relate, as a sheltered kid coming from high education and low finances, who discovered the big world with quite a splash, when I was teenager, too. In the smoke of burning Los Angeles instead of the pyres at Dashashwamedh Ghat.

Picking up Pankaj’s first novel was an impulse; I didn’t know what I was getting into. I was swept away by the soulfulness of Samar’s coming of age, and the fact that it took place in a scene of what I would call my own massively displaced nostalgia: post-revolutionary India — the decades after the 1947 revolution.—

Nostalgia, for me? I’ve never been to the Indian continent; I’ve only lived in its legacy.

“Pretend I was born in India.

“I’ll wind your worn sari around my shoulders and waist. I’ll take your bright pink lipstick and put a mark on my forehead. We’ll pretend that all the freckles are gone.

“I’ll bathe in lemon juice and they’ll disappear. My hair will be so black, glossy, and long I can sit on it, or wind it up on top of my head like Sita.”

— Big Sex Little Death, S.B.

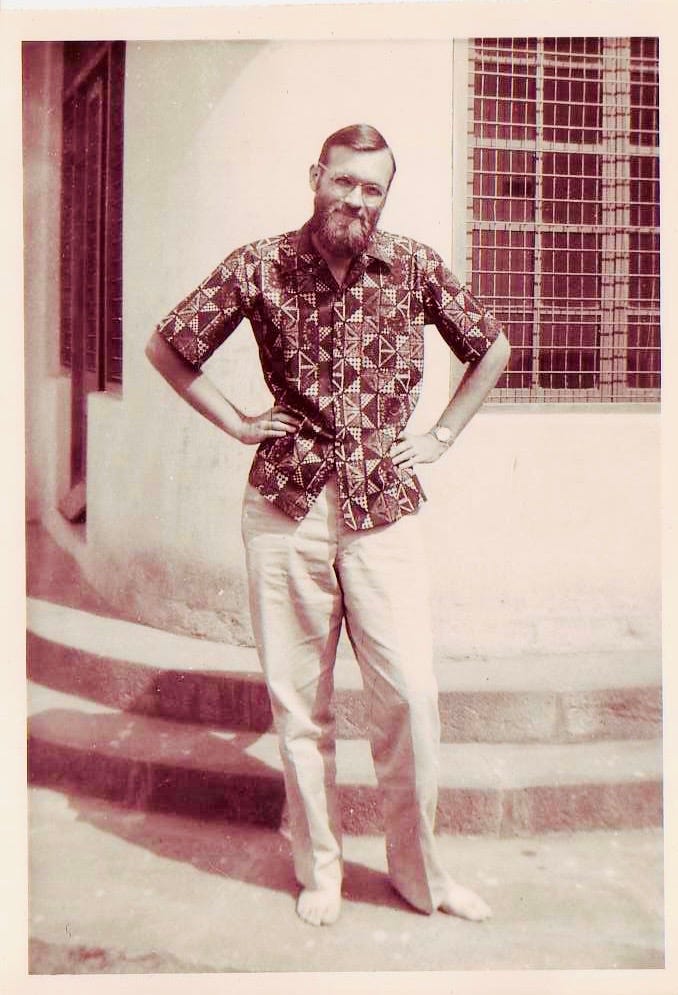

My parents, Elizabeth and Bill, moved to Pune, Deccan College, to study in the mid-1950s, after my father’s release from the Army. Like so many expatriates who stumble into something just because they got a “job,” both of them came to feel they found their home, intellectually and aesthetically, far from California (dad) and Minnesota (mom).

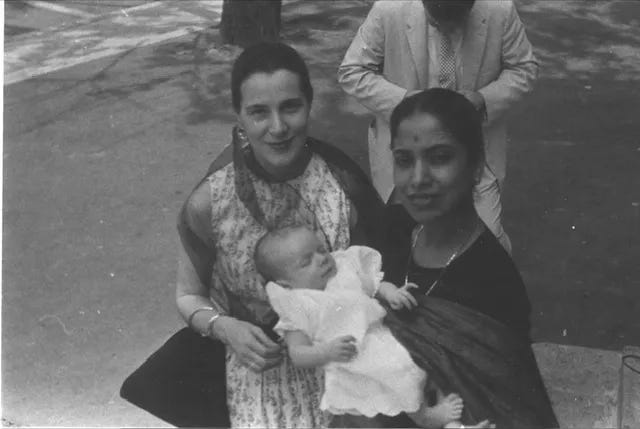

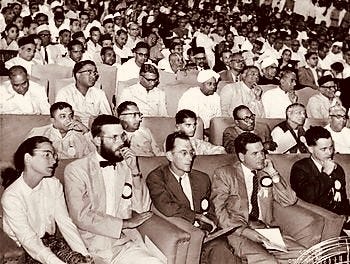

I never got to ask Mama about her time in India with my grown-up perception. But what on earth was it like, to be the only woman in this sea of Brahmin Sanskrit scholars in 1956? That’s her, in the left corner of the photograph:

India wasn’t a hippie trek for Bill and Elizabeth— my parents’ time in India was long before the American sixties fad of yoga and enlightenment. They were linguists; a different kind of inquiry! —Devoted to Sanskrit, Urdu, Tamil, Kannada, Hindi dialects and language community of all kinds.

They were also intoxicated with the “hope” that was in the air in Nehru’s India, the idea that social equality and freedom from British colonial rule— and the caste system, by extension— had a chance to live. They were reading R.K. Narayan in the moment, as he was writing stories for the daily newspaper. I have their scrapbooks from those years, where they glued all their favorite headlines and advertisements.

Long after they returned to Berkeley at my birth in ‘58, after their ‘60 divorce, one thing stayed the same between their trajectories: looking back at India. Two kinds of music on their record players (okay, plus Pete Seeger): Western classical and Ravi Shankar. The latter was the first live concert I remember, falling asleep on my daddy’s shoulders at Occidental College.

My mom moved a lot, we had no furniture; and yet I can always remember her burning a bit of incense from her jam jar of sandalwood to “clear” a new apartment we moved into, the empty room. She would put her tiny bronze of baby Krishna with his ball of butter, on the mantel or a windowsill.

At Christmas, when we put the wooden infant Jesus in his crèche, devised by my feverish scissors; creation of “hay” —shredded yellow foolscap— I asked if we could put Krishna next to Jesus so he wouldn’t be lonely. And so they stayed, quite mixed up in my mind, for years to come.

The Romantics does not take place in the 1950s — It unfolds during the author’s university years, which I believe took place in the late 1980s, first in Uttar Pradesh, and then during his wandering years in Banaras, and finally, the Himalayan valleys.

Banaras, or as Mishra writes it, “Benares,” is now more well-known by its Hindi name, “Varanasi” —and yes, that switch is political. It’s the nerve of those who want to claim, exclusively, one of the most ancient human and spiritual settlements we know of! (1800 BCE).

But the old names, many of them, aren’t so easily forgotten.

The events set in motion by the 1947 revolution — the fight between “Can’t we imagine a better future?” vs. “Death and corruption are our karma”— it’s all there in young Samar’s sojourn to the mother river.

I kept daydreaming our hero might run smack into my parents at the Central Library, the city’s tribute to The British Museum, built by a maharajah in 1941. My fanfic! Yet this is what the story engenders, finding your history in it.

Dum vita est, spes est.2

How did this Indian history — so close, so far— pepper my life?

Well, living in Berkeley3 in its great renaissance, was my cradle. UC Berkeley brought Indian scholarship to the United States. Our family’s life, food, our friends, was filled with campus and Telegraph Avenue characters much like Mishra’s and Narayan’s wanderers: displaced Brahmins, raised to do naught but study (much like rabbinical students), who’d sometimes been stripped of their family money, or seen generations of demise, much like the post-Civil War plantation descendants, who “lost it all” in dissolution and disgrace. They lost their lands.

So— privilege without money, tortured post-colonial classconsciousness, and a belief in “the life of the mind,” tempered by the frustrations of dealing with the here and now. (Kamala Harris’ mom knew this world well — she was at UC Berkeley in 1958, too).

I never got to travel to India with either one of my parents. I really don’t know how to do it without them. Everyone they knew, that generation is gone.

My father would say, “someday we’ll ride every Indian second class bench on the trains,” just as he traveled, on the wide and narrow gauges. I would watch movies like The Darjeeling Limited, and pine for the occasion. It just didn’t come to be.

Today, Hindu nationalism has torn India’s secular dreams to smithereens— as Mishra has described in his political non-fiction like, Age of Anger.

I know there is still a there there, but I fear I would not know how to find it. I don’t relate to the Goa crowd, that’s for sure. Film, maybe? Perhaps through libraries, and cinemas, just like our novel’s young searcher, Samar.

Mishra himself found great creative opportunity and peace when he left the ghats for the Himalayas, and from there, he moved to the next long journey of his life, to London.

My father returned in the Sixties to India, now as a UCLA professor instead of starving student, and again enjoyed a great love affair with all he encountered. (I don’t think my stepmother Marcia had the same epiphany. It wasn’t her soul-space; I see her painful jaundiced passport photo, speaking volumes).

In 2004, when my mom was at the end of her life, in an Iron Range nursing bed, she showed me a photo she said “was the happiest time of my life” — in Pune. It was a black and white ragged-edge picture, outside her and Bill’s tiny apartment near Deccan College. My partner Jon drew a charcoal portrait of the photograph for her, that we posted on the wall, and she would gaze upon it, smiling, in her morphine dreams. I believe that portrait helped her die in peace.

So… back to this book, The Romantics. If you listen to my audio passage at the top, you’ll know immediately if you succumb to my enchantment.

Finding the book, for me, was a fluke, and a pretty rugged search. You can find one yellowed digital copy on the Internet Archive. I heartily recommend applying for low-vision free access!

I discovered Mishra’s titles because heard his London lecture on Palestine — it blew me away.

(Text version here).

It wasn’t the man’s politics which surprised— those I share.

The shock was his oratory. Anyone who can speak like that, WRITES.

So I ordered all Mishra’s works from my public library, and I gravitated to finding out his origins. The Romantics’ blurb intrigued: “Mishra defends the ability of literature to explain deeper truths or, as Nadine Gordimer puts it, “Nothing factual that I write or say will be as truthful as my fiction.”

To my surprise, The Romantics is not e-book! -Not in audio. What is going on with his literary agency? I’m ready to read the whole thing aloud on YouTube and torture you with my Hindi impersonations.

Mishra, in his recollections about the novel, tells us that “Samar” (i.e., himself) also fell in love with a foreign book that informed his young life: Gustav Flaubert’s Sentimental Education. It was written in the 19th century, a classic setting of a young person, easily touched, who find himself in revolutionary times.

Mishra fell into Flaubert, his first coup de foudre, because of the author Edmund Wilson’s 1937 treatise on Flaubert’s and Karl Marx’s politics. —The pleasure of essays that change our lives, leading to one thing to the next!

Well, what a coincidence: I was once in teenage love with Edmund Wilson, too! Among many kindred spirits, I’m sure.

I read Wilson’s To the Finland Station on a cross-country Greyhound bus in 1974, in transit to a socialist cabal. Ha. Finland Station is a great book to make the hours fly by across the prairies. It is a history of the gestalt and characters, who from the French Revolution to the dawn of Bolshevism, formed the intellectual dream of social equality, what would come to be called “socialism.”

It’s the only book in the world that makes you feel like you met Lenin for a drink on the train and a vigorous argument at the gates of the 20th century. Wilson’s such a great poet/writer, which is more than I can say for most of his subjects. ;-)

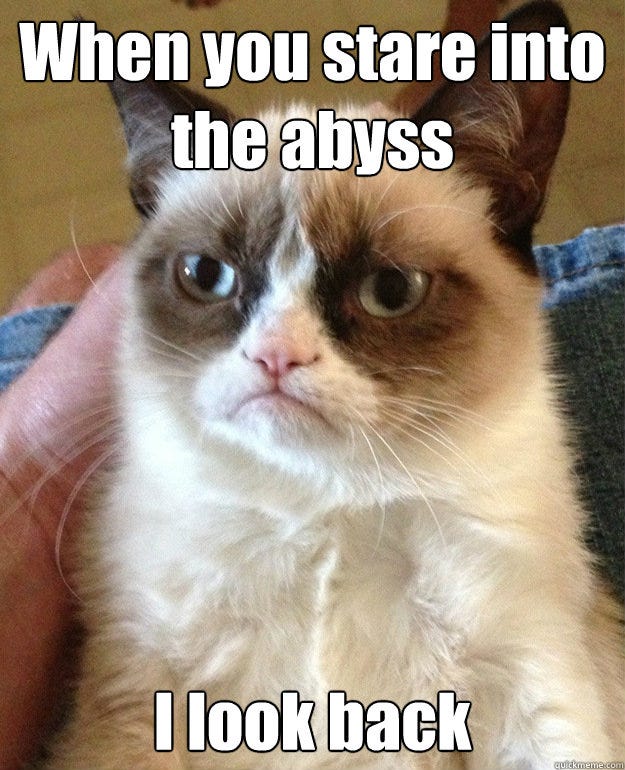

In journalist Sarah Fay’s Believer essay on Pankaj Mishra, she notes, “When I asked him what those of us living in modern countries in the West can learn from [his] sagacious skepticism, he referenced a quote from Nietzsche: “If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

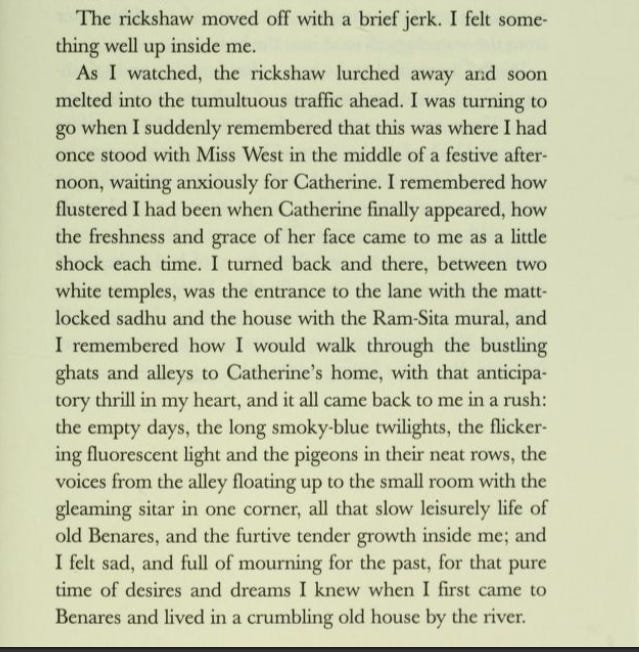

Let me read one last passage before I leave you be. It’s at “The Romantics”’ penultimate page:

As I watched, the rickshaw lurched away and soon melted into the tumultuous traffic ahead. I was turning to go when I suddenly remembered that this was where I had once stood with Miss West in the middle of a festive afternoon, waiting anxiously for Catherine.

I remembered how flustered I had been when Catherine finally appeared, how the freshness and grace of her face came to me as a little shock each time.

I turned back, and there, between two white temples, was the entrance to the lane with the mattlocked sadhu and the house with the Ram-Sita mural, and I remembered how I would walk through the bustling ghats and alleys to Catherine’s home, with that anticipatory thrill in my heart, and it all came back to me in a rush: the empty days, the long smoky-blue twilights, the flickering fluorescent light and the pigeons in their neat rows, the voices from the alley floating up to the small room with the gleaming sitar in one corner, all that slow leisurely life of old Benares, and the furtive tender growth inside me; and I felt sad, and full of mourning for the past, for that pure time of desires and dreams I knew when I first came to Benares and lived in a crumbling old house by the river.

MORE

Ready to go down the author’s rabbit hole? It’s quite enjoyable.

Sarah Fay recalled the career turning point in Mishra’s trajectory: “After submitting an article on Edmund Wilson to the New York Review of Books, Mishra was “discovered” by the journal’s renowned editor, Barbara Epstein.”

His career took off. Below are some of his early works I’ve particularly enjoyed, before he became well-known for his political work on contemporary politics in the Middle East.

An End to Suffering: The Buddha in the World, [the fascinating story of Buddha has a man vs. the myth vs Western discovery -SB]

India in Mind, a historical anthology of writers on India (Twain, Ginsberg, Gore Vidal, et al)

Temptations of the West: How to be Modern in India, Pakistan, Tibet, and Beyond. [If that titles sounds a wee sarcastic to you, you’re right!]

Introduction, Rudyard Kipling (Kim)

Introduction, R. K. Narayan (The Ramayana)

Introduction, E. M. Forster (A Passage to India)

Introduction, J. G. Farrell (The Siege of Krishnapur); and my mother’s favorite,

Introduction, V. S. Naipaul (Literary Occasions: 11 Essays).”

Mishra’s bloody takedown of Niall Ferguson.

Village Magazine interview during Mishra’s Age of Anger book tour, in Ireland.

Modernization is offered as Liberation Yet With Many Psychic Costs

Why Panjav wrote The Romantics, at Yale Review:

Excellent Loggernaut interview

Glossary

Ghats, ghaats, “Gahts”: a grand flight of steps leading down into a river. In the book’s case, the many historic river steps along the river Ganges.

Pathan, “Pah-TAHN”: a variant spelling of Pashtun, as in “His Pathan suit.” It’s the three-piece formal traditional suit an Indian man wears to a wedding, and other special occasions.

Matar Paneer, “Mah-TAR Pah-NEER”: peas and cottage cheese

Bhaang, “Bahhhng”: Cannabis, as in, Bhaang-laced Tea

Thandai, “Tahn-DIE”: a sweet Indian drink made from a milk base with ingredients such as almonds, saffron, and poppy seeds. Yum. Like Indian horchata.

Taaj, “TAHJ”: Crown

Shyam, “Shahm”: Character’s name, but also “swarthy.” Saying he is the family retainer— he is their full time, round the clock servant.

Parathas, “Partas”: Parathas are thick, flaky flatbreads made from whole wheat flour. They can be plain or stuffed with potatoes, vegetables, or meats. You eat with curries, chutneys, or yogurt.

Chulha, “CHUL-hah”: Hearth fire

Lanka, “LAHN-kah”: Ceylon (Colonial name), Sri Lanka

Lahtis, “Lah-tees”: Truncheons, the clubs the police and thugs beat you with

The “Indo-Saracenic Revival,” per Wiki, was an architectural style mostly used by British architects in India in the later 19th century, especially in public and government buildings in the British Raj, and the palaces of rulers of the princely states. It drewfrom native Indo-Islamic architecture, especially Mughal architecture, which the British regarded as the classic Indian style, and, less often, Hindu temple architecture.

Havelis, “Hah-VELL-ies”: Old mansions

Chaudhry Faiz Ahmad Faiz, just called “Faiz” was a Pakistani poet and author of Punjabi and Urdu literature. He was one of the most celebrated, popular, and Urdu writers of his time. He’s the one whom Samar’s mobster friend adores, almost to the exclusion of reading anything else, and the joke is that the sentimental “new age” vibe of Faiz is in stark contrast to the life of the reader!

“The Bofors scandal” was a major weapons-contract political scandal that occurred between India and Sweden during the 1980s and 1990s, initiated by Indian National Congress politicians and implicating the Indian prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi.

Pallu, “PAL-oo”: the loose end of a sari, worn over one shoulder or the head. You are always rearranging your pallu!

Shenai, “SHA-nai”: Indian version of a clarinet

Churidars, “Choo-ri-DARS: also churidar pyjamas, are tight-fitting trousers worn by both men and women. They are usually cut on the bias, an important quality for close-fitting garments. They are also worn longer than the leg, sometimes being finished with a snug, buttoned cuff at the ankle.

Halwai, “HAL-vai,”: The Candymaker. The word means an Indian caste and a social class, whose traditional occupation was confectionery and sweet-making. The name is derived from the word Halwa which is a sweet dish.

Lunghi, “Luung-hee,”: a men’s garment, a floor length skirt like a sarong, wrapped around the waist. You wear it when it’s hot, and yes, without a shirt, it’s very sexy.

Chana, “CHAH-na,”: Chana masala (also chole masala or chholay) is a chickpea curry cooked in a tomato based sauce.

Ayodhya, “Ay-YAH-Dee-Ya”: Ayodhya is an ancient city in Uttar Pradesh, the birthplace of Lord Rama, a significant figure in Hindu mythology.

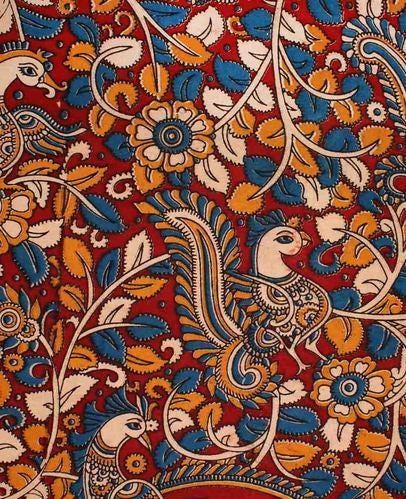

Kalamkari, “Kah-lum-KAH-ri”: Traditional textile decoration technique of Andhra Pradesh; it’s hand-painting and block-printing on mordanted fabric.

In Case You Missed It

“A bildungsroman is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood, often depicting their journey of self-discovery and maturation. The term comes from the German words for “education” (Bildung) and “novel” (Roman).”

While there is life, there is hope

I am a literal conception of two post-WWII Berkeley ‘seekers. If my DNA sprang from any philosophy it’s this one-of-a-kind place, yet I’ve never read the breadth of its history like this essay.

One of your best, so heartfelt yet full of energy and love.

Here I am.

Shouldn’t there be a warrant out for the arrest of Jonathon Ross based upon his own cell phone evidence? And warrants for every other ICE agent present as accomplices?

THE COMMON GOOD MANIFESTO

A society built for people, not predators.

We are at our best when we invest in each other.

We are at our worst when we abandon the vulnerable.

This manifesto is how we return to the common good.

I. DIGNITY AND JUSTICE

1. Release the Epstein files — full transparency, no exceptions.

2. Impeach, convict, and imprison Donald Trump and every handler who enabled his corruption.

3. No federal office for any convicted felon.

4. End the weaponization of the justice system against the poor, immigrants, LGBTQ people, and marginalized communities.

II. DEMOCRACY THAT ACTUALLY WORKS

1. Abolish the Electoral College — one person, one vote.

2. Abolish ICE — replace it with humane immigration policy that honors human rights.

3. Ban gerrymandering with a standardized national apportionment method.

4. Two-term limits for every elected office.

5. Mandatory retirement at 70 for all elected officials.

6. Paper ballots only — end the era of hackable voting machines.

III. AN ECONOMY THAT SERVES PEOPLE

1. Restore 1950s-style progressive tax rates — when America was prosperous and fair.

2. Overturn Citizens United — corporations are not people.

3. Eliminate the Social Security payroll cap and tax capital gains for Social Security contributions.

4. $25 minimum wage indexed to inflation.

5. Medicare for All, one unified system — no A/B/C/D maze.

6. Congress receives Medicare, not boutique private insurance.

IV. WORKERS, CREATIVES, AND PUBLIC SERVANTS

1. Big pay raises for social workers, teachers, librarians, artists, and cultural workers — the people who actually hold society together.

2. Universal childcare — because families are the foundation of the nation.

3. Free public university education.

4. Full forgiveness of all student debt.

V. CLEAN GOVERNMENT

1. Root out corruption at every level, starting at the top.

2. Full financial transparency for every elected official, appointee, and senior bureaucrat.

3. Ban lobbying for former officeholders for life.

VI. THE FUTURE WE CHOOSE

We choose a country that values:

• Compassion over cruelty

• Community over greed

• Truth over propaganda

• Shared prosperity over billionaire hoarding

• Democracy over minority rule

• Human dignity over corporate profit

We choose a nation where the common good is not a slogan, but the organizing principle of public life.

And we refuse to apologize for demanding better.