“Things People Know About Language That Ain't So”

A story from my father on the politics of language

Well, today is a little different.

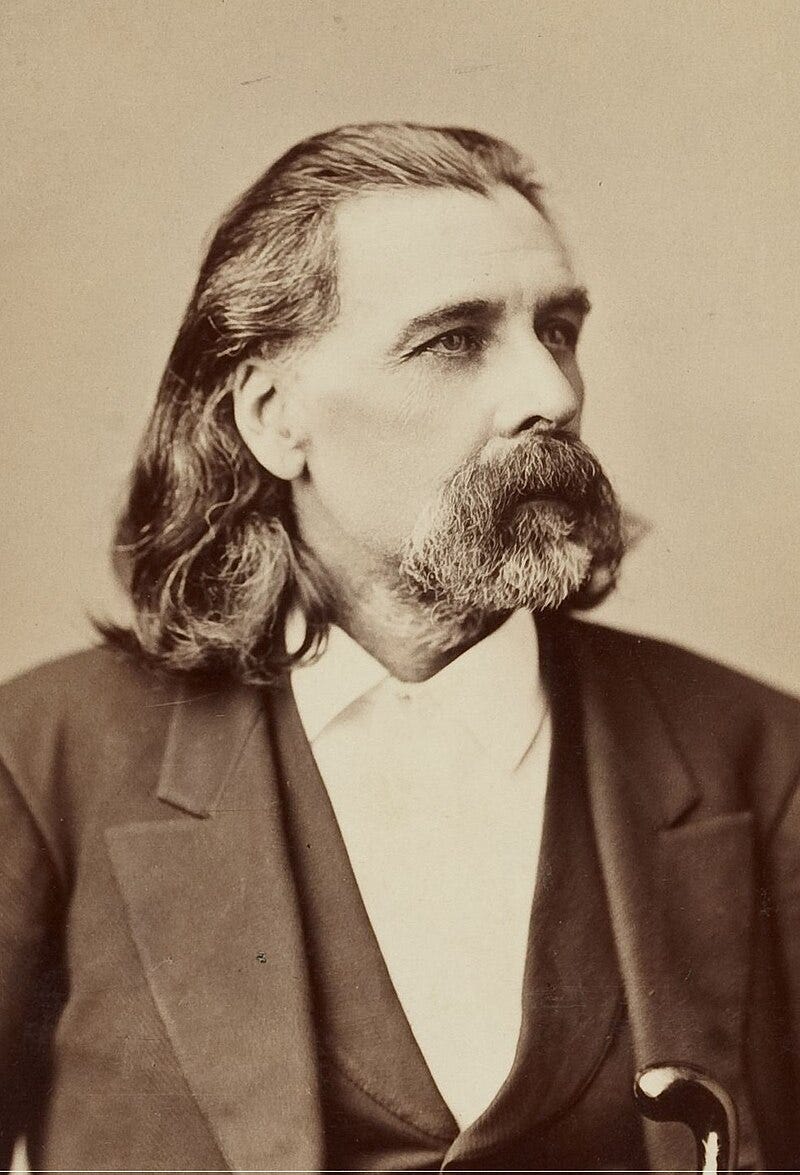

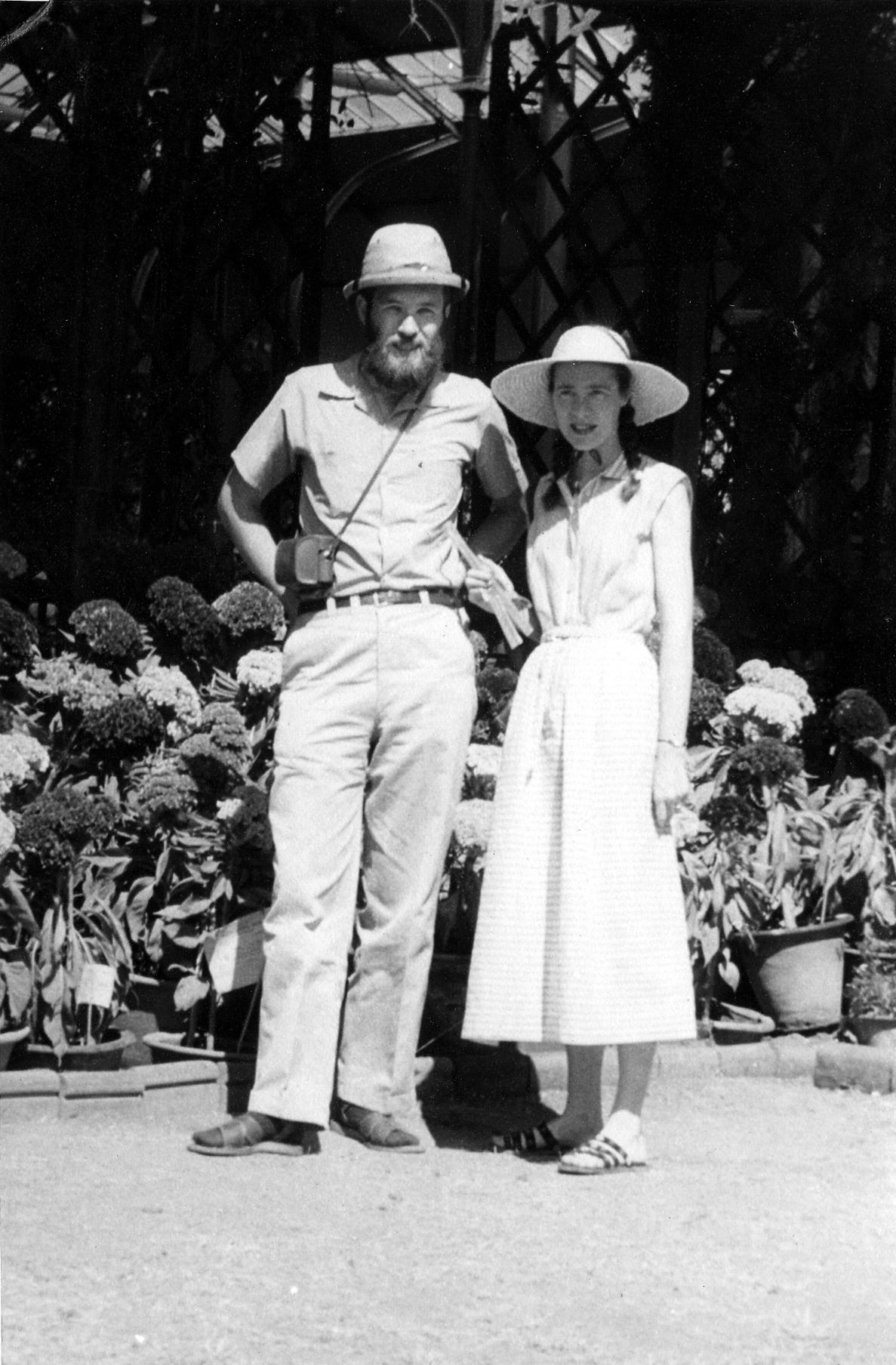

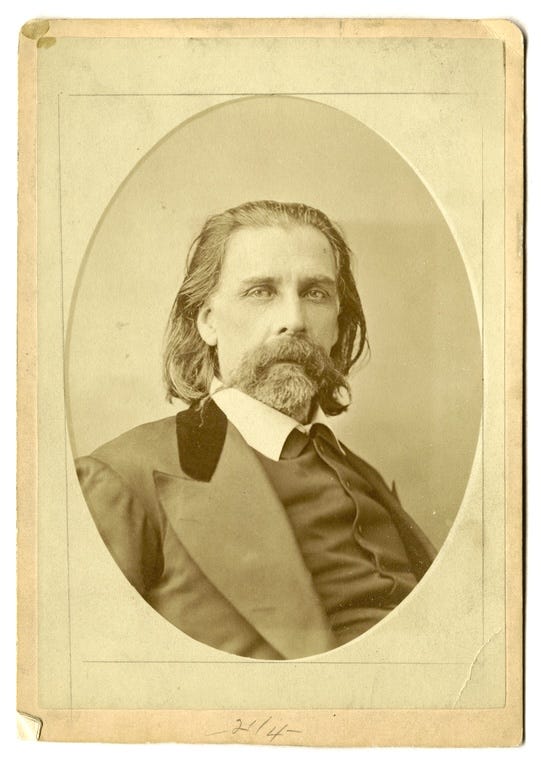

I’m running the following historical essay by my father, Bill Bright. He wrote it in 1976, when I was 18, and he was 48.

It’s an article that, to my chagrin, I’ve only now taken an interest in, in my dotage.

I was close to my dad, Bill Bright— he was a linguist, and he taught me to edit very young, by letting me sit on his lap with a red pencil to try and find printers’ errors in the galleys he worked on every night.

—Just a pencil, because I couldn’t yet be trusted with a pen.

I still don’t think I can be trusted.

Bill could magically speak and write every language, but because he was my daddy, I took it for granted. I can’t tell you how many powwows and brush dances and lost places, deserts and mountains, where I would sit around in his shadow, not understanding any of the words, but getting ideas, nonetheless.

When he started in linguistic studies after WWII, all his peers (a small bunch) wore white Oxford button-downs, and skinny black ties. By the early sixties, the same crowd started sporting sandals and beards and having a healthy dislike for US imperialism.

Also, their departments were being infiltrated by the CIA. 1

The following story, with its comic name, has been cited in dozens of publications, which makes me think it was influential in its time. It was the beginning of social scientists asking the question, “Who’s an expert?” —Which would lead to, in some cases: “Do we have to account for researching culture that our ancestors destroyed in the first place?”

Note: I typed this story manually from its original publication in an obscure Slavic Languages journal, (impervious to scanning). I made light edits to make it more readable online. I’ll include the original PDF file at the conclusion.

William O. Bright

From a paper given at a conference on sociolinguistics in Eastern Europe, held at Penn State, Oct 24-26, 1976.

The title of this paper is based on a quotation from the 19th-century American humorist Josh Billings, who said: “It is better not to know so much than to know so many things that ain't so.'

I like this quote for several reasons. It is a healthy warning the academic profession, whose stock in trade is what we “know.” We are reminded that the “knowledge” of one scholarly generation may become, in a later era, a discredited hypothesis.

A second reason why I like the Billings quote is because it is interesting as a sentence of English: although perfectly grammatical, it is semantically deviant, in that there is a contradiction between the meanings of the verb know and the phrase to be so.

Yet it is plain that the sentence is not meaningless; our semantic competence as speakers of English permit us, somehow, to resolve the apparent contradiction, and to recognize that the sentence is not only meaningful, but also true, and even interesting.

These observations, however, do not explain my main motive for quoting Billings.

The real reason the quote is relevant is because we can apply it to what the speakers of a language know about their native tongue— on what members of a speech community “know” about their linguistic repertories.

What is the status of such “knowledge”?

Does it ever happen that people “know” things about their speech that simply “ain’t so”?

To consider these matters, we need first describe the kind of “knowledge” with which we are concerned. I used the term “competence” — I understand this to be definable, as “what a speaker knows about his own language.” I take the description of that knowledge as a goal of linguists.

But such knowledge is of different kinds. Some of its parts are phonological rules, which permit us to recognize the English word blik but not bnik as a possible word of English.

Some are morphosyntactic rules, which enable us to reject “I aren’t” as ungrammatical; still others are semantic rules, which help us identify the title of my essay as deviant, but meaningful.

I am pointing to several type of knowledges which are usually the COVERT, rather than the OVERT expressions of speakers.

Unless the speaker of English is a linguist, he will probably never formulate the generalization which rules out bnik; nevertheless, he has tacit or implicit knowledge of that generalization.

There is no question about the validity of such implicit knowledge; if the native speaker knows it, it is so.

There is a contrasting type of “knowledge” about language, which is not covert at all, but is taught. This “knowledge” comprises the pieces of misinformation that we try to knock out of students’ heads in introductory linguistics courses: that so-called “primitive peoples" have rudimentary grammar; or that speech is somehow the step-child of writing; that linguistic change is evil; or that "there ain't no such word as ain’t."

Such specimens of linguistic folklore have a certain interest, but no linguist is likely to fall into the error of attributing any factuality to them.

There are further types of linguistic “knowledge,” however, which deserve the sociolinguist’s attention. Consider the native speaker who, rather than asserting that the phrase "he ain't" is not English, asserts that it may exist in English, but is ungrammatical.

This position will put him in conflict with many linguists, who would prefer to say that while "he aren't" is ungrammatical— it must be ruled out by a grammar of English— "he ain't" is non-standard, yet quite grammatical. Descriptive rules for English grammar account for it.

These contrasting positions may create confusion for the linguistic researcher; but it is a harmless kind of confusion, since it will disappear as soon as the native speaker and the linguist can agree to use the word "grammatical" in the same way.

Similar discrepancies arise between linguists’ "knowledge" and native speakers’ "knowledge" as to the identification of particular languages. Linguistic textbooks, often used to contain the teaching that Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish were a single language on the grounds of mutual intelligibility.

At the same time, however, the people of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark went on unconcerned in the "knowledge" that they spoke three separate languages.

Since the rise of sociolinguistics, linguists came to agree with the native speakers’ position.

The criterion of mutual intelligibility has little usefulness in classifying dialects into languages. The linguist must fall back on the social and political criteria which are used by the native speaker.

Similar examples can be found in eastern Europe; for instance, I learned that Macedonian is regarded in Greece and Bulgaria as a dialect of Bulgarian, but in Yugoslavia, it is considered a separate language.2

Another interesting example, rather closer to home is described in a recent dissertation by Lucia Elias-Olivares on Chicano speech in Austin, Texas, 1976. In this setting, adults often stated that their teenage children do not speak Spanish, whereas the young people insist that they do. As Dr. Elias says, "The problem is, "What are we calling Spanish?”

For the young people, a sentence like, Jui al swimming pool (“I went to the . . .”) is Spanish, but for the parents it is not.

Such discrepancies can have serious political effects, as we can see in the post-colonial history of India. For some decades, the idea that political boundaries should correspond with language boundaries has been popular in India, and in 1957 there was a reorganization of state boundaries on the principle that each major language should have at least one state corresponding to it— a Tamil state, a Bengali state, etc.

But problems arose in assigning certain regions to major languages. The most serious dispute was in the former Punjab state, where the population was split between two religious groups, the Sikhs, and the Hindus— which also constituted political factions.

By the linguist’s criteria, all these people spoke the same Punjabi language. With regard to written language, however, there was a difference. The Sikhs who were literate used the Punjabi language in a script of their own, called Gurmukhi.

Literate Hindu normally did not do any reading or writing at all in their native spoken language, Punjabi– rather, they learned to use Hindi in the Devanagari script, for these purposes.

On this basis, Punjabi-speaking Hindus reported their native language not as Punjabi, but as Hindi – even if they were not literate in ANY language.

This caused such confusion in the census data for languages that the Census of India conducted in 1951 simply gave up any attempt to distinguish Punjabi from Hindi.

Ultimately, Hindi became the symbol of Hindu identity in the Punjab— and Punjabi, the symbol of Sikh identity— to such an extent that in 1961, the national government was forced into carrying out a partition. Then we had two nominally linguistic states: Punjabi Subah, primarily populated by Sikhs, where Punjabi is both spoken and written— and Haryana, primarily populated by Hindus, where Punjabi is spoken, but Hindi is written.

This partition raised a problem with regard to the beautiful capital city of the old Punjab state, Chandigarh, which had been designed by the Swiss-French architect, Le Corbusier. The ultimate solution was that the boundaries of both new states were drawn right up to the city limits of Chandigarh, which was designated as a Union Territory, not part of either state.3

However, the governmental offices were split down the middle. The Punjabi Subah High Court, and the Haryana High Court, for instance, ended up on opposite wings of the same building in a capital city, which was not part of either state.

Let us turn then, to a type of "knowledge" which falls more squarely within the area of what my colleague Del Hymes4 has taught us to call "communicative competence.”

The problem is this: we all communicate in a variety of codes— languages, dialect, or registers— depending on social factors such as our own roles, the roles of others, and our surroundings.

By the time we are adults, we usually KNOW pretty well what codes will be appropriate in most circumstances. However, it sometimes happens that the covert, tacit “knowledge” which determines our behavior of spontaneous communication, is not the same as the overt, verbalized "knowledge" which comes to the fore when we are self-conscious about our speech.

The phenomenon I am referring to is related to the question of "language attitudes." In a survey of this field, Cooper and Fishman quote a definition of language attitudes, from an unpublished paper by Charles Ferguson, as "elicitable should's on who speaks what, when, and how.”

I like the definition, but it refers to only part of the topic— I am interested in cases where there is a discrepancy between "elicitable should’s" and actual behavior.

In 1955 I went to India to do research on the Kannada language. In my last four months before leaving California, I studied the language with a Kannada-speaking student, a doctoral candidate in political science. I thought I had a foundation in the language.

However, when I had arrived in India, and settled down in Bangalore (the capital city of the Kannada-speaking state), it turned out that the language I heard on the street was hardly recognizable to me.

Eventually, I found that the situation was an example of what Ferguson was later to make well-known under the name of diglossia: there was a formal Kannada, used for writing, stage acting, speechmaking, or teaching one's language to foreigners— and there was an informal Kannada used for normal conversation.

The formal style was archaic and prestigeful; but the informal style was characterized by phonological change— and was not only lacking in prestige, but was completely outside the awareness of many educated people, especially those trained in the humanities.

In fact, when hiring college students to tutor me in the language, I soon learned that although science or engineering majors could provide me with good models of informal speech, the history and literature students had been brainwashed to the point where they no longer had consciousness of their own colloquial styles.5

For example, the formal Kannada for "he doesn't do it” is, in the Brahmin dialect, māḍu-vudilla; the informal equivalent, showing extensive deletion and contraction of sounds, is māḍolla.

If a typical person educated in the humanities is asked whether he ever says māḍolla, he will typically deny it; if he is played a tape recording, made surreptitiously of his own conversation in which he, in fact, says māḍolla, he will be flabbergasted.

Situations like this are reported from all over the world. For instance, in describing the speech of the Norwegian town of Hemnes, John Gumperz discussed the shift, during informal conversation among townspeople, from forms of the local dialect to forms of bokmål (standard Norwegian):

"When the conversation turned to abstract issues of other than purely local reference, open network groups6 showed higher incidents of bokmål. However, personal switching and open network groups is independent of expressed attitudes to language. . . When tapes of one discussion were played to a member of a second group, they first claimed that participants could not be Hemnes residents.

“The same tapes were played back to one of the discussion participants, who expressed surprise. She did not realize that she had been code-switching. She expressed her intention to avoid extensive switching in the future.”

Nevertheless, "Tapes of subsequent discussions show little change. . .

When an argument required that the speaker validate their status, as an intellectual, they would again tend to use standard forms."

Similar differences between self-reports and overt behavior were reported from American English by William Labov:

"The normal practice of linguists is to elicit a speaker’s ‘competence’ under formal conditions where language itself is the object under study. When we do so, we are dealing directly with the speaker’s evaluation norms: what he considers ‘good,’ ‘proper,’ and ‘correct.’ The linguist will himself reject any overt expression of such ideas as nothing but a "secondary reactions to language.

“But when he uses linguistic data produced under such formal conditions, the data is screened through such attitudes. Most native speakers do not know, or will not admit, how strong their attitudes towards language are.”

Speakers can make distinctions in formal tests— which they do not make in everyday speech.

We can see that if we want accurate information about speech behavior, it is not enough to simply ASK people about it, nor indeed to observe their behavior in the highly structured situation of speech elicitation.

We must find ways to observe their SPONTANEOUS speech.

This is not a new recommendation; Labov and others have already taught us a great deal about this. Even so, many sociolinguists are still gathering data by means of over-the-desk interviews, questionnaires, and other types of self-report.

I do not condemn those techniques as such, but I would urge that they be supplemented in every case with techniques for observing non-self-conscious behavior.

The second point that I want to emphasize about spontaneous and non-spontaneous behavior, is that they are BOTH SIGNIFICANT.

The non-spontaneous responses are misleading, if we want to learn about people's normal speech behavior.

But they are prime data, if we want to learn what people believe about their speech.

Thus Kannada speakers may know perfectly well when to say, mādu-vudilla, and when to say, mādolla.

But in another sense, they may also "know" that, so to speak, "there ain't no such word as mādolla.”

The sociolinguist needs to take both kinds of "knowledge" into account, because the knowledge of things that "ain't so" is not an error: it is an expression of deeply-held values.

What people know about their languages includes material about the choices of sociolinguistic variants. That material in turn includes formulations which do not describe normal speech behavior, but which embody IDEALS, associated with that behavior.

The sociolinguist must distinguish the knowledge that governs spontaneous behavior from the knowledge of these ideals— but this does not mean that the latter are to be ignored as errors.

As ideals change in strength within a speech community, they may affect the success of language-planning efforts— or, the course of normal linguistic change.

Let me note that unrealistic ideals regarding speech behavior may be held by linguists too, when they are members of the relevant speech community.

Such ideals may have an effect on linguistic scholarship. In India, Dr. D.P. Pattanayak, director of The Central Institute of Indian Languages, published an article in 1975 in which he downgraded the importance of dialect variation correlated with caste— a topic on which there is extensive literature.

Indeed, Pattanayak suggested that "the talk about caste dialect may have negatively reinforced caste identities and feelings.”

This seems to me, an attempt to discount objective data in favor of an ideal. It reminds me of an experience which visitors to India often have, when they are told by idealistic Indians, that untouchability no longer exists7 or that caste no longer exists, because these institutions have been abolished by law.

Most visitors find out, of course, that the reality is different.

Another commentator, K.M. Tiwari, offered a trenchant paraphrase and interpretation: “Dr. Pattanayak is implying that the notion "caste dialect" is not only "unscientific and unnecessary," it is positively harmful to our body politic.

“Ours is a secular, democratic and socialistic state; in our society castes should not exist; if they exist, they should be overlooked; if the castes have linguistic consequences, the linguists must not talk about them for fear of ‘negatively reinforcing caste identities and feelings’ . . .

(This is being said sarcastically; sound familiar?- SB)

“If I read Mr. Pattanayak’s intention right, he is trying to cross sociolinguistics with social and moral hygiene. He is, of course, entitled to whatever psychological satisfaction he gets from this exercise, but it does not add much to the effectiveness of his strenuous attempts…”

I would only add that, however, misguided Pattanayak may be, his idealism is itself a sociolinguistic phenomenon worthy of attention, and one which we may expect to encounter anytime, in any part of the world.

CITES

Blom, Jan-Petter, and J . J . Gumperz. 1972. "Social Meaning in Linguistic Structures: Code-Switching in Norway." Directions in Sociolinguistics, ed. by J. J. Gumperz & Dell Hymes, 407-34. New York: Holt.

Bright, W. 1976 . "Comments on Pattanayak 1975." International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 5:65-68.

Cooper, Robert L., and Joshua A. Fishman. 1974. "The Study of Language Attitudes." Language Attitudes I , ed. by Robert Cooper (International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 3), 5-20. The Hague: Mouton.

Elías-Olivares, Lucía. 1976. "Ways of Speaking in a Chicano Community." Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

Ferguson, C. A. 1959. "Diglossia."Word 15:325-40.

Gumperz, John J. 1966. "On the Ethnology of Linguistic Change." Sociolinguistics, ed. by W. Bright, 27-49. The Hague: Mouton.

Haarmann, H. 1965. Soziologie und Politik der Sprachen Europas. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

Hoenigswald, H. M. 1966 . "A Proposal for the Study of Folk-Linguistics." Sociolinguistics, ed. by W. Bright, 16-26. The Hague: Mouton.

Hymes, D. H. 1962. "The Ethnology of Speaking." Anthropology and Human Behavior, ed. by T . Gladwin & W.C. Sturteveant, 13-53. Washington, D.C.: Anthropological Society of Washington.

Hymes, D. H. 1974. Foundations in Sociolinguistics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Labov, William. 1974. "Linguistic Change as a Form of Communication." Human Communication: Theoretical Explorations, ed. by Albert Silverstein, 221-56. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Labov, William. 1975. "On the Use of the Present to Explain the Past.” Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Linguists, Bologna 1972, ed. by Luigi Heilman, 825-51. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Pattanayak, D.P. 1975. “Caste and Language." International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 4:97-104.

Rickford, John R. 1975. "Carrying the New Wave into Syntax: The Case of Black English." Analyzing Variation in Language, ed. by Ralph Fasold and Roger Shuy, 162-83. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Tiwari, K. M. 1975. "Comments on Pattanayak 1975." International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 4:361-64.

In Case You Missed It

Would you like to contribute to my newsletter without pay-subscribing? I get it. A single, one-time “tip” makes all the difference too.

Read late anthropologist Sally Binford’s gripping account (search for phrase, “enter the CIA” about how UCLA’s anthro and linguistic departments became CIA battlegrounds. She and my dad were colleagues.

(Haarman, 1965).

SB: Here, my father was writing in 1976, and I’m not clear what has happened in Punjab state since then. Considering President Modi’s nationalism, I am guessing if anything, it’s gotten worse! Please update me in comments . . .

(1974:75)

Humanities! ROTFL!

Refers to social groups characterized by flexible and dynamic relationships among their members, a wide range of interactions and exchanges. —As opposed to "closed network groups," where relationships are fixed, exclusive.

In 9th grade, I was flunked in Social Studies by my Emerson Junior High School teacher in Los Angeles, when I objected to her stipulation that caste had been eradicated in India. “But that’s not true!” I said, “that’s ridiculous!” and so I was given an F. That is the one time my dad came into the school to go to bat for me. Teacher’s revenge went on all year . . .

Great picture of your parents!

Thank you so much for posting this! It has me thinking about Southern Studies, and how there are certain scholars performing certain kinds of southernness at conferences and on campus. (My goodness, the seersucker!)