The Time Has Come the Walrus Said

The end of childhood on the borderline

The same spring my dad wrote me about my stepmother’s death, my mom got two other letters in the mail. Both of them were from attorneys. They’d been given her address by my father, after having searched for her without success for over a year.

I walked in the door from school. Stomping the snow off my boots. It snows in Edmonton well into May. “My sister and my father have died,” Mom said. Her voice cracked when she said, “my sister.”

I knew not to say anything; to leave her be and make supper.

A few weeks later, she said, “I’m going to send you to your father’s this summer; it’s time he did something for a change.”

I was careful not to show any expression. If I was happy, she might take it back. I just said, “Okay.”

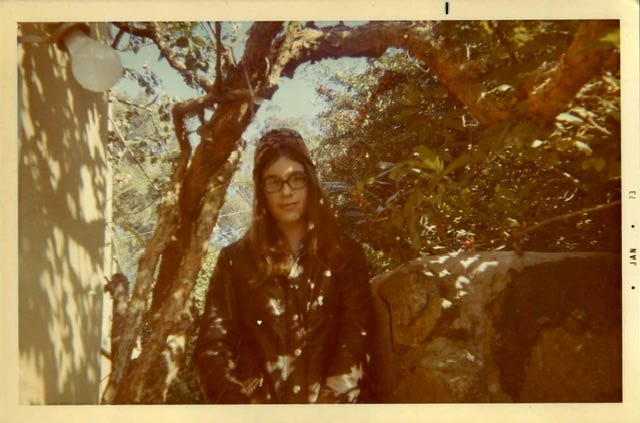

In June, I took a plane to Vancouver to meet my dad. That way I didn’t have to cross the Canada-US border alone. I hadn’t seen him in two and a half years. I was 14.

I didn’t know what to call my father when I saw him. Was I too old to say “Daddy?” Nothing else seemed to fit. W…