Real Thirsty Coyote Stories

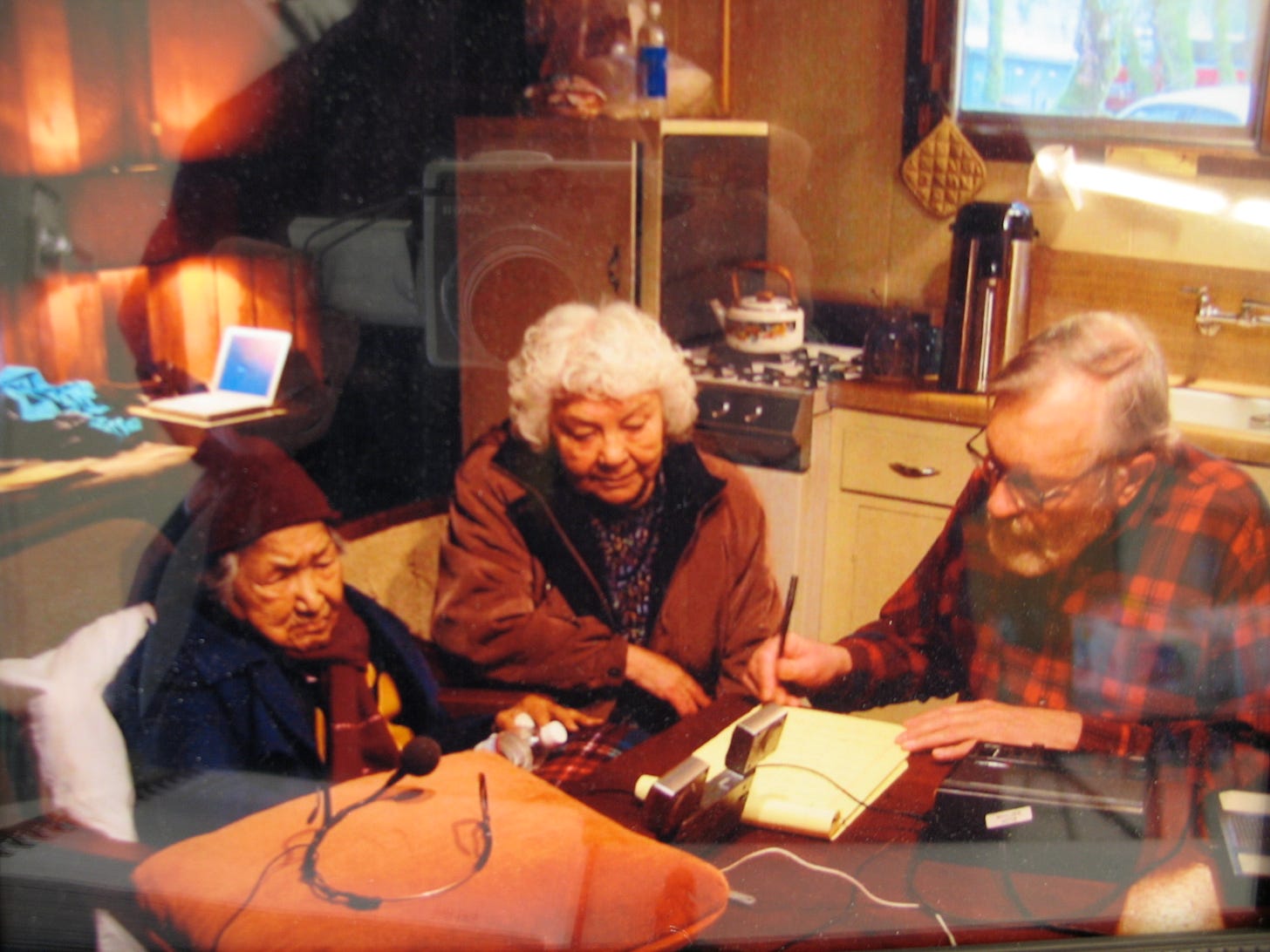

Bill and Susie, on the legends you grow up on

Today I’m going to tell you some of the Coyote stories I grew up with, that I learned from my mother and father and all the aunties and uncles who hung out a certain time in a certain place.

Most of them are from Klamath River country in far northern California, and what is now called Humboldt and Siskiyou counties.