Re-location

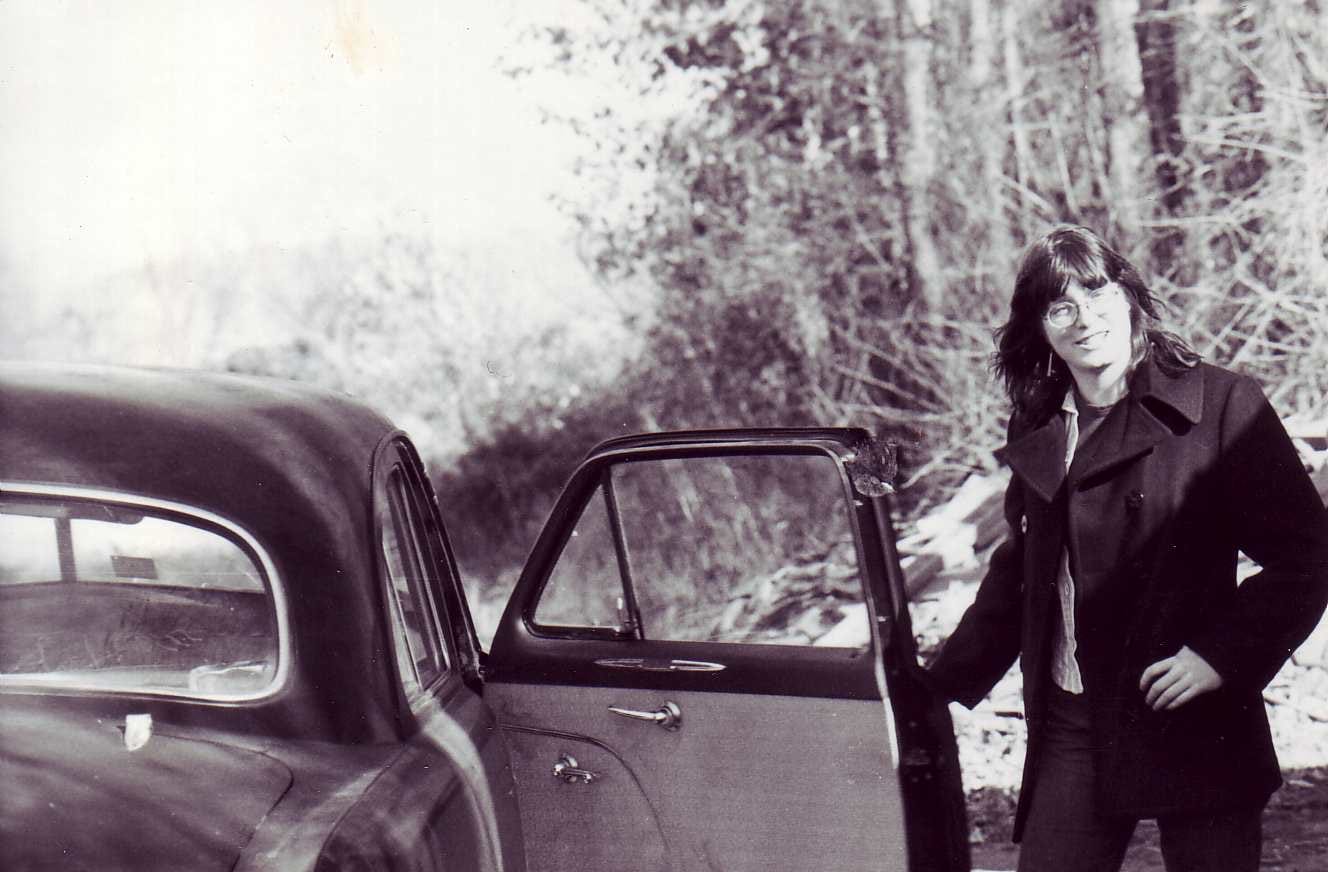

Louisville Runaway, 1975

Jack Bloom was still in the hospital, but he was stable. Seventeen stab wounds to the chest, and he never lost consciousness. His wife told me when she got him out of there, she was getting out of the I.S. for good. I wondered if she’d have any trouble convincing him.

Everyone was supposed to get “back to business.” Every morning, we’d begin with a meeting, and after we stopped donating blood, we weren’t supposed to talk about Jack anymore. Move on, don’t look back. There was a revolution waiting and others suffering with much worse.

I agreed with the last part but not with the silent treatment. I was a malingerer.

The morning meetings began at Larry’s Diner downstairs, with the coffee and donut order. Red, another comrade from East Oakland, would ask me for money for a donut.

“Why are you asking me?”

“You look like a rich white girl.”

“You are high.”

“Always, always, sugar pie—” and then he’d hit up Frank. And then Bushy, and then Steve P. Finally one of t…