Porn Argument Road Shows: Squaring Up the Racket

Every time the rescue industry swings into action, they go for B-movie Tactics

At the height of the feminist sex wars, a lurid X-rated slide show toured college campuses, designed to alarm its audiences to the perils of pornography. It was produced by self-described feminists.

It was a fever-inducer. And it drove me up the wall. I was a feminist who didn’t agree with them, and they said there couldn’t be an argument.

There was an argument.

I responded with two show-and-tell's of my own: "How to Read a Dirty Movie," and "All-Girl Action: The History of Lesbian Eroticism in Hollywood."

The following essay is a review contrasting our two presentations; the so-called "sex positive" and the "anti-porn."

I never read a critique of either of our shows which was more than, "Oh my god, they're showing nekkid people doing it!"

This review, therefore, was fascinating for me and I've always been surprised more people haven't considered it.

Writer Eithne Johnson's story is scholarly, published in a film geeks' journal. It’s detailed. I wish her insights had been discussed in a broader milieu, because they are evergreen. They don’t always make me look good, but that’s not the point— it’s fresh air to get some objective reporting.

I'm glad to show it here, in digital form at last. I've included some of my own corrections and reactions in italics.

Porn Education Road-Shows

A Critique by Eithne Johnson

from Jump Cut, no. 41, May 1997

In April 1995, MIT graduate students organized a public panel discussion in reaction to a private strip show that had been sponsored by male students in a dormitory.

Offended by the idea of this strip show, the graduate students ambitiously wanted their panel to address the issues that they felt it raised: "prostitution, stripping, and pornography."

Following advice from friends, faculty, and on-line respondents, the panel organizers decided to provide a "balanced" panel by setting up "pro" and "con" sides. Thus, they imposed this binary opposition on the speakers who (warily) agreed to participate.

"Pro" panelists included Kim Aires, "a sacred sex worker" and sex shop owner; Cynthia Chandler, a Harvard Law School student who was under consideration for Playboy's "Ivy League" issue; and me, Eithne Johnson, a media studies instructor and researcher on women's porn.

"Con" panelists included Northeastern University professor Jackson Katz, founder of the "anti-sexist" group "Real Men", attorney Sally Hunt, who defends street prostitutes; and sociology professor Gail Dines, "renown lecturer on the pervasiveness of the media in our MTV culture" (from the program).

For the organizers, this panel was a feminist political response to the pressing problem of sexism on campus, epitomized for them by the strip show.

For me, the panel was cause to reflect on the many porn-related panels that I have organized, participated in, and/or attended over several years. Given that I had once been a student activist, I could relate to the students' desire for an immediate and feminist-identified response.

However, I was dismayed that the anti-pornography argument, to which they devoted the lion's share of the evening, had already shaped their understanding of feminist media criticism.

Following on thirty years of women's activism, feminist media presentations, such as the anti-porn slide show, deserve more critical attention precisely as spectacles that use media for polemical education and advertising critique.

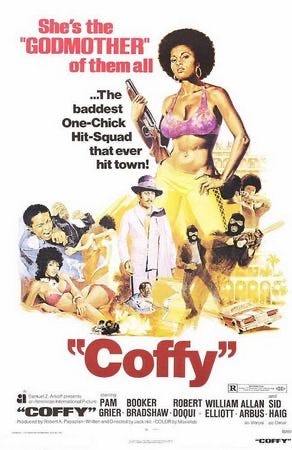

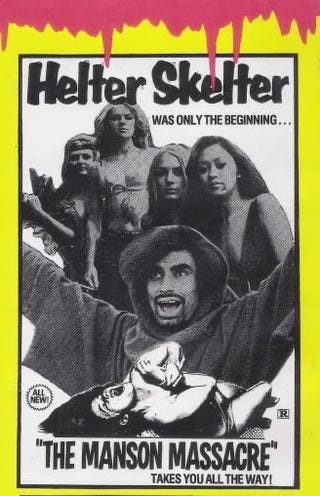

Since the early-to-mid eighties when X-rated movie screenings became the target of campus protests, a marginal space has emerged for feminist speakers who "educate" college audiences about the perils or pleasures of pornography, which may be defined so broadly as to include advertising and slasher films.

As you probably know, these feminist educators typically use slide shows or video clips as their main attractions.

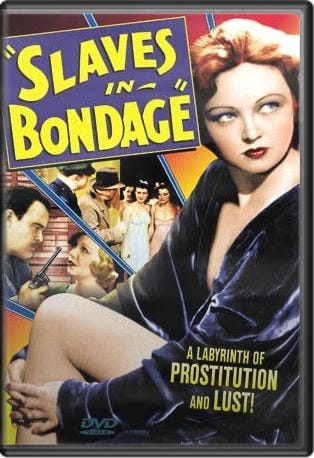

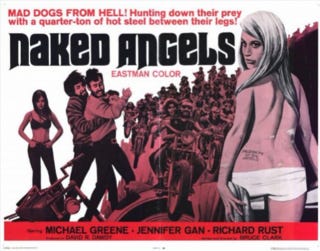

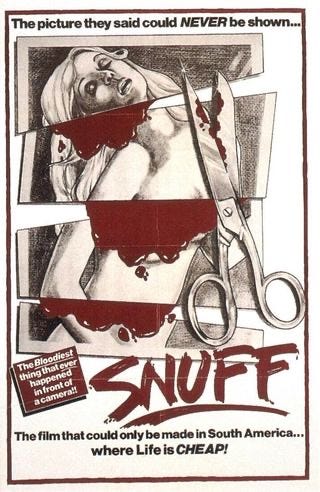

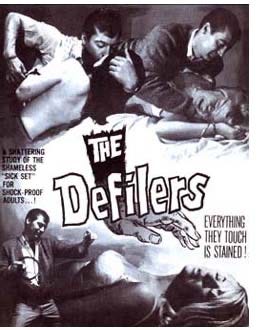

That these spectacles purport to instruct even as they promise to titillate and/or terrify their audiences suggests a strategy similar to the exhibition practices of "classical" exploitation roadshows.

According to Eric Schaefer, because the "classical" exploitation film existed in a "space between" reputable cinema and disreputable (stag) films, producers were motivated to claim an educational value for their lurid pictures. Like the "classical" exploitation exhibitor, these feminist speakers offer hybrid pornographic/ educational roadshow attractions. As itinerant performers, they exploit the "space between" the official curriculum and extracurricular activities, which not so long ago could include porn movie screenings.

Here I will consider two prominent figures on the feminist roadshow circuit who exemplify the two types of spectacles — "anti-porn" and "pro-sex."

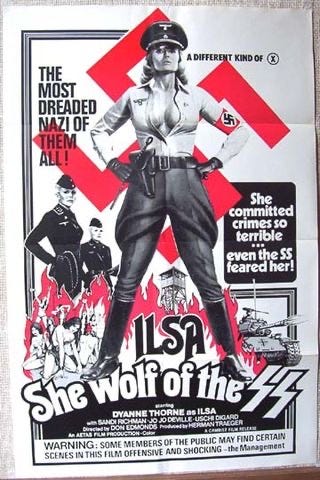

Wheelock College professor Gail Dines is opposed vehemently not only to pornography but also to much of popular culture because both perpetuate "images of violence against women" (publicity).

Writer/editor Susie Bright is a pro-sex feminist who encourages women to explore pornography for its range of sex fantasies and to contribute to the genre.

In this essay, I will look at the ways in which these pornographic-educational roadshows reconstruct pornography as a reading practice while also creating marginal venues for discussions of sexual agency and sexual abuse.

Two discursive tactics are deployed: 1) the anti-porn roadshow defines pornography as patriarchal propaganda for violence against women, illustrated by images from porn, advertising, and horror movies; 2) the pro-sex roadshow defines pornography as a genre in order to show its mutability as a cultural form and its accessibility to women as producers and consumers. Both moves reconstruct pornography through interpretive readings that depend on the appropriation of pre-existing images.

Formally, they recall the "compilation" type of the "classical" exploitation film. Thus, the anti-porn slide show compiles images that read pornography as the "objectification" of women: the educator (Dines) locates female victims upon whose symbolically posed bodies will be found traces of a now-absent male perpetrator.

The pro-sex video show compiles scenes that read pornography as the representational territory for sexual fantasies: the educator (Bright) celebrates pornographic scenes that exemplify female sexual agency and erotic pleasure.

It is important to reflect on the advantages and disadvantages imposed by using "pornographic" images as both the catalyst for and the organizing principle of feminist educational events.

What does it mean that these pornographic/ educational roadshows have appeared in reaction to popular entertainments (X-rated movies, strip shows) that promise pornographic spectacle? How do they teach women to read pornography and what are the implications of such education? To address these questions, I will show how pornographic/educational roadshows function as attractions.

BALLYHOO AND SELF-PROMOTION

Hoping to lure straight men for instant consciousness-raising, the MIT organizers promoted their panel to appeal to implied male consumers: "A Buyer's Guide to Prostitution, Stripping, and Pornography." On the promotional flyer, the catchphrases "LIVE GIRLS" and "Equality of the Sexes" appeared in light and dark print respectively, promising both pornographic entertainment and educational debate.

While exploiting pornography's generic imperative to reveal live flesh, the organizers sought to persuade attendees to take an "educated" position according to the "pro" and "con" factions seemingly represented by us, the panelists. This balancing act made the evening tense for us since we were precisely set up to become spectacular. For the audience, it delivered the ultimate battle between pornographic/ educational roadshows, pitting pro-sexers against anti-pornographers.

The audience did not know that the terms of the engagement had been rigged from the start, as I will explain. However, as such campus spectacles go, the unannounced strip act by "sacred sex worker" Kim Airs was probably the exception rather than the rule. This was clearly more LIVE GIRL than the organizers expected to see, even as they had unabashedly promoted the event with such ballyhoo.

Gail Dines and Susie Bright also negotiate the distinction between the "serious" educator and the entertaining LIVE GIRL according to their discursive tactics. Both cultivate visibility within the public sphere, are represented by agents, and have appeared on talk television.

For Professor Dines, the anti-porn discourse opens up a channel for official institutional support. For example, she was scheduled at Emerson College in April, 1995, under the auspices of the Dean of Students Office and the Committee for Awareness Programs at Emerson. "Seriously" entitled, "Sexy or Sexist? Violence Against Women in the Media," her presentation was accompanied by publicity from her agency calling it, "A Powerful Slide/Lecture Presentation by Gail Dines, Ph.D." Here, a photo of Dines, posed austerely in professional attire, appeared bottom-right, visually counterbalancing a sexy fashion photo upper-left.

Even as this semiotic display exploited the education/entertainment divide, Dines' credentials served to situate her roadshow as seriously instructional:

"Drawing upon research by sociologists, psychologists, feminists and media scholars, Dines will examine how these images affect the way we think about ourselves as males and females, as sexual beings and as potential victims and victimizers."

Suggestively linking sex and violence, this anti-porn discourse proposes to preempt any pleasure associated with explicit imagery by framing heterosexuality in terms of the "objectification" theory: female = object/ victim; male = subject/ victimizer. The disciplinary educator promises to reveal the latent meaning of pornographic imagery through the re-representation of the LIVE GIRL as victim.

It comes as no surprise, then, that Dines not only supported local protests against an adult video store in Boston (as did fellow panelist Jackson Katz), but she also brought Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon to testify for their controversial anti-porn ordinance before the Massachusetts legislature.

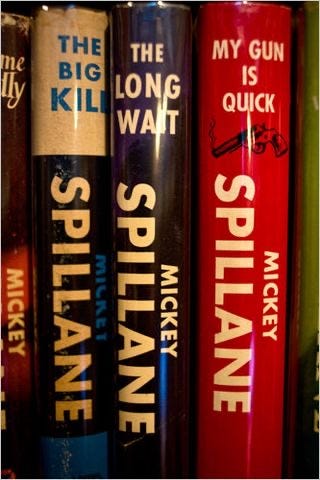

Because the anti-porn roadshow created a space for "serious" feminist educators, it has dominated the scene from the college campus to Capitol Hill. At the same time, it has engendered resistance to its polemical "objectification" thesis. Bright's pornographic-educational roadshow emerged out of the feminist pro-sex and anti-censorship movements, with which she identifies, given her history as sex toy specialist at Good Vibrations, a film reviewer for Penthouse Forum, and the founding editor of On Our Backs, which dared to play off the more "serious" feminist publication, off our backs.

Like other women porn producers, Bright seeks to subvert the prevailing anti-porn argument by countering it as an informed consumer/connoisseur. In this way, she implicitly claims to be subjectified, not objectified through pornography. Not only does Bright reject the distinction between "good" erotica and "bad" pornography supported by anti-porn feminists, but she incorporates the generic promise of the LIVE GIRL into her own performances and her promotional materials.

In 1987, Bright hit the college circuit, beginning with Cal Arts; she was also welcomed at gay/lesbian film festivals. Her first roadshow was titled "How to Read a Dirty Movie," featuring a video compilation. She followed with another video compilation roadshow, "All Girl Action, The History of Lesbian Eroticism in Hollywood."

Her roadshows tend to be supported by gay-lesbian-bisexual groups either on campuses or outside official institutions. In Austin in 1990, "How to Read a Dirty Movie" was part of the Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, while "All Girl Action" was "sponsored by the Women's Media Project" (Maher).

At Williams College in 1995, Bright's "Sexual State of the Union Address" was sponsored by the Dively Committee, the BGLU, the Lecture Committee, and the Theatre Department. As a self-appointed, bisexual-lesbian spokeswoman for the LIVE GIRL, Bright occupies a more marginal position on the campus roadshow circuit than Dines, whose institutional affiliation secures her status as a legitimate educator.

As a "sexy" performer, Bright seeks to challenge the limits of women's respectable behavior in public; for Dines, institutional codes set limits on dress and behavior that can affect career opportunities.

SHOW-WOMANSHIP

A pornographic/educational roadshow succeeds as an attraction to the degree that the educator fulfills the ballyhoo's promise to deliver a spectacular performance. True to her "serious" publicity photo, Dines performs as a Marxist-feminist vanguardist. (This is interesting news to me, since I also think of myself as coming from Marxist and feminist foundations... SB)

Dines' agency markets her roadshow as a humane mission; statistics on the incidence of rape, battery, and molestation of females (whether or not accurate) are meant to shock.

As an agit-prop performer intent on persuasion, Dines has sought to control the impact of her presentation before it even begins. On the eve of the MIT event, organizers admitted they had allotted Dines more time for her slide show than the entire "pro" side combined. The students justified the disparity by saying that Dines would not participate unless they gave her a minimum of 20 minutes, which was all she would agree to edit her 45 minute show down to. She has purportedly set rigid terms at other events as well.

According to Jim D'Entremont and Bob Chatelle of the Boston Coalition for Freedom of Expression, they invited Dines to participate in a debate at Boston University regarding the anti-porn ordinance then supported by Dines, Dworkin, and MacKinnon. At the event, Dines refused to debate the other panelist and took questions only from students.

After taking up much more than her allotted time, Dines summarily left the panel, followed by a group of supporters. (D'Entremont and Chatelle suspect that the audience was stacked with several of Dines' students from nearby Wheelock College.)

The other panelist, a woman with much experience defending civil liberties and supporting women's shelters, had little time to present her argument against the anti-porn ordinance, much less to contend with an audience that was greatly disturbed by Dines' rhetoric.

The rabble-rousing anti-porn performance appears to demonstrate the triumph of the disciplinary educator over pornography's perversity. Emotionally moved audiences obviously find something gratifying in this victory in rhetoric. By refusing to debate, democratic dialogue is suppressed in favor of moral indignation.

Whereas Dines issues radical-critical theory warnings about popular culture's seductiveness, Bright revels in seduction's consumerist pleasures. In performance mode as "Susie Sexpert," Bright wants to be the "bad" girl to the "good" women of anti-porn feminism. Like porn stars-turned-performance artists, Bright uses her body to deconstruct the theater of pornography, its sexual stylings and fantasy constructions.

Her sartorial choices as Susie Sexpert signify her cultivation of perversity: she embodies a connoisseur of pornography, the pleasure-seeking, sexually subjectified consumer which anti-porn feminism has traditionally denied to women and ceded to men.

Unlike Dines, who has an appointment at an academic institution which gives her economic security, Bright has a much less secure occupation as "freelance writer, editor, and lecturer."

Dines' roadshow may be motivated by Marxist feminist politics, but she does not have to tour for a living. Bright has financial reasons to stay on the lecture circuit as well as on book tours (sometimes simultaneously). Indeed, Cleis Press (one of my first publishers- SB) markets Bright as a pop culture commodity/ connoisseur: "America's favorite X-rated intellectual" (publicity).

Since Bright has to consider the possibility of future gigs, she probably has to give a "good" performance" to be invited back. Criteria for judging her performances would emphasize their entertainment value and inclusiveness of sexual identities; of course, official discourses can also deploy these very criteria to withhold legitimacy to her lectures. Few academic programs would actually hire her as a self-styled "X-rated intellectual," (I actually haven't found that to be true, particularly in private universities- SB) but she has taught the occasional class, including a course, "The Politics of Sexual Representation," at UC Santa Cruz (her alma mater).

In contrast, Dines' academic credentials authorize her performances as an educator, seemingly removed from the realm of commodities. As a professor, her words have weight; however, if her presentation were subject to peer review, it might have attracted a lot more critical attention from media scholars by now.

THE "SQUARE UP" OR HOW TO ATTRACT AUDIENCES BY ALARMING THEM

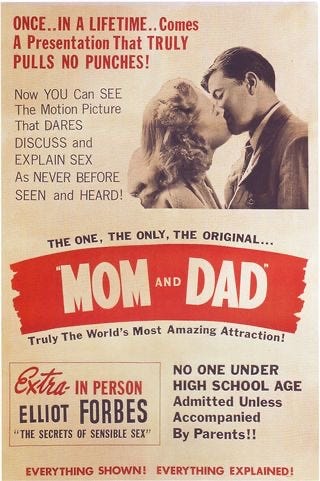

As Eric Schaefer explains in his dissertation, the "classical" exploitation film typically began with a "square up": "a prefatory statement about the social or moral ill the film was attempting to combat". Purporting to provide a somber educational perspective, the "square up" served as a moralistic pretense for showing the lurid spectacle which the film promised its audience.

Schaefer points out that roadshow advertising ("exploitation" as it was then called) played up such pictures' edifying and titillating aspects. For films dealing with sexual matters, audiences were even segregated by gender, an exhibition strategy that could be seen to support a conservative take on sexual relations (even if it was only meant to safeguard the box office). Pornographic/ educational media presentations also use the "square up" tactic, especially those that promote an anti-porn argument.

Indeed, anti-porn presentations perpetuate an inherently conservative, segregationist model of gender relations by setting up a female victim against a male victimizer. Because this strategy is used by porn opponents on the far right and the radical left, it deserves further scrutiny. In asking people to identify with the quintessential victim — the young girl — such educational presentations talk down to their audiences in order to scare them into the correct reading.[6]

Before discussing the "square up" for Dines' presentation, it is worth comparing two videos that promote anti-porn positions: Sut Jhally's DREAMWORLDS (1990) and Focus on the Family's LEARN TO DISCERN (1992).

Offering a radical critique of gender on MTV, DREAMWORLDS opens as follows: "Warning: This video contains scenes of graphic sexual violence which may disturb some viewers."

Then the title appears followed by the subtitle, "Desire/Sex/Power in Rock Video." While the warning sets up the expectation for exposure to "graphic sexual violence," without explaining what constitutes such, the subtitle then suggests erotic excitement.[7]

Since both violence and erotica can be emotionally unsettling, the warning primes audiences to become disturbed. The opening sequence explains that MTV was designed to target teens, but the accompanying visual imagery (taken from a music video) implies that the real target is young girls, echoing the anti-porn argument's claim that the true victim of a pornographic culture is the female child.

From a critical Christian perspective, LEARN TO DISCERN opens with a similar warning directed toward parents presumably ignorant of how popular culture puts their children "at risk," especially the innocent girl.

Not surprisingly, heavy metal iconography figures prominently in both DREAMWORLDS (as sexist imagery) and LEARN TO DISCERN (as satanist imagery). Though from opposite ends of the political spectrum with regard to gender relations and capitalism, both videos incorporate the feminist anti-porn strategy of linking "pornographic" images (from porn, MTV, advertising, and slasher films) with violence against women. Seeking to impose fear, DREAMWORLDS exploits the theme music from HALLOWEEN; LEARN TO DISCERN is shot with a studio audience, so reaction shots of disturbed faces bolster the educator's lecture.

This "horror show" approach has proven very effective attracting and provoking audiences, from students to senators.[8]

As an exhibition practice, the "square up" helps position the educator as expert (on media, on female victimization), and therefore most competent to read popular imagery. To prepare people to see Gail Dines' presentation at Emerson College, the Director of Student Activities issued the following memo:

"Please be advised that the slide presentation will contain adult content and that children under 18 are discouraged from attending."

(What better way to prime an audience of college students than to warn them of "adult content?") Attached to the memo, Dines' publicity flyer provided a provocative warning that was posted all over campus:

"On a daily basis we are bombarded with media images that suggest sexual harassment is flirting, battery is foreplay, and rape is hot sex. Using examples from advertisements, films, magazines, MTV, and 'slasher' movies, Gail Dines shows how images of violence against women are so commonplace that we, as a society, are becoming desensitized to them."

Dines' "square up" sets up an expectation to be "desensitized," presumably by viewing an atrocity exhibit of "violence against women." While Dines repudiates these images as dangerous to women, her slide show exhibition compels her to inflict those same images on her largely female audiences.

Given that Hitchcock's notorious quote — 'Torture the women! The trouble today is we don't torture the women enough" — appears at the top of her publicity flyer, she seems to have learned something important from this Hollywood showman. Hitchcock, DePalma, slasher films, and made-for-TV movies have exploited audience sympathy for female characters-as-victims.

Similarly, Dines wants to generate and exploit such sympathy in order to win adherents to anti-porn feminism. Even as the anti-porn educator urges women to become "image-literate" (so they are aware of this "violence"), anti-porn discourse preempts individual women's competency to read popular imagery by presenting only one correct, disciplined reading. If any woman finds the imagery erotic, then she is left to conclude that such pleasures must be guilty.

(At this point, you might like to know that Dines shifted emphasis since her antiporn roadshow days. She is now the central American figure fighting "sex trafficking", and her politics on prostitution reflect the same views she portrayed in her antiporn work. - SB)

Because Susie Bright seeks to challenge anti-porn discourse, she uses the "square up" tactic in seeming parody. Her first roadshow, titled "How to Read a Dirty Movie," echoes the anti-porn educator's assumption that audiences need to be taught a proper way to read porn. Thus, Bright's "square up" beckons an audience already sensitized to anti-porn discourse. As Bright explained to reviewer Kathleen Maher,

"It's very much like an erotic literacy tour...A lot of it is about gender and then I talk about what people mean when they talk about violence in pornography" (21).

Like Dines, Bright claims the educated reader's position, but from personal experience rather than formal education. To counter the anti-porn presumption that (good feminist) women are porn-illiterates, pro-sex discourse issues from a s/expert — a feminist whose consumer/producer experience with the genre qualifies her to explain it. For her sexpertise, Bright draws on her impressive background as reviewer, performer, and consultant for sexually explicit films.

Whereas Dines' "square up" warns audiences about harmful violent images, Bright subverts the tactic by warning audiences of the dangers of a feminist discourse that fails to acknowledge women's pleasures in and production of sexually explicit imagery.

In fact, Bright wants to champion porn — especially its non-normative "girl-girl" convention — and selected film imagery as sites in which lesbians could locate and read female sexual desire in a society that has refused direct representation of lesbian sexuality.

With "All Girl Action, The History of Lesbian Eroticism in Hollywood," Bright promises to reveal the pleasures of "deviant" readings.

(I was, as you might be guessing, influenced by John Berger's "Ways of Seeing," and Vito Russo's "The Celluloid Closet" - SB)

Unlike Dines' show, which attempts to close down alternative readings, Bright's show opens up space for multiple readings and interpretive competencies. Moreover, she does not talk down to her audiences nor ask them to assume a universalized position of the innocent young girl.