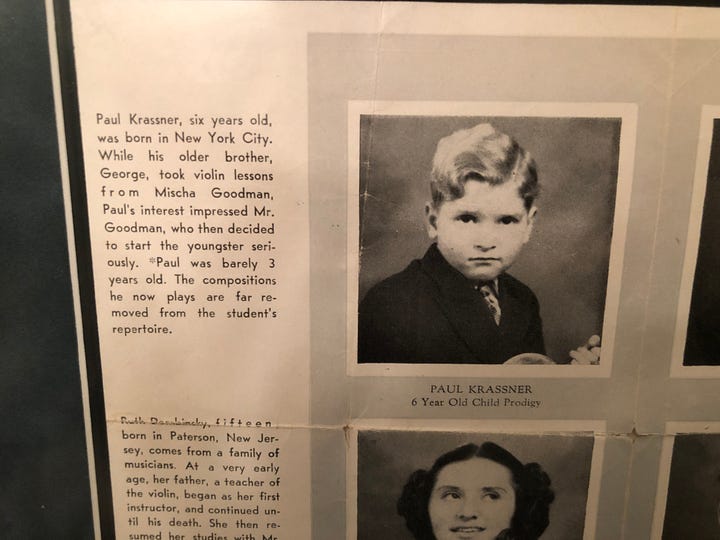

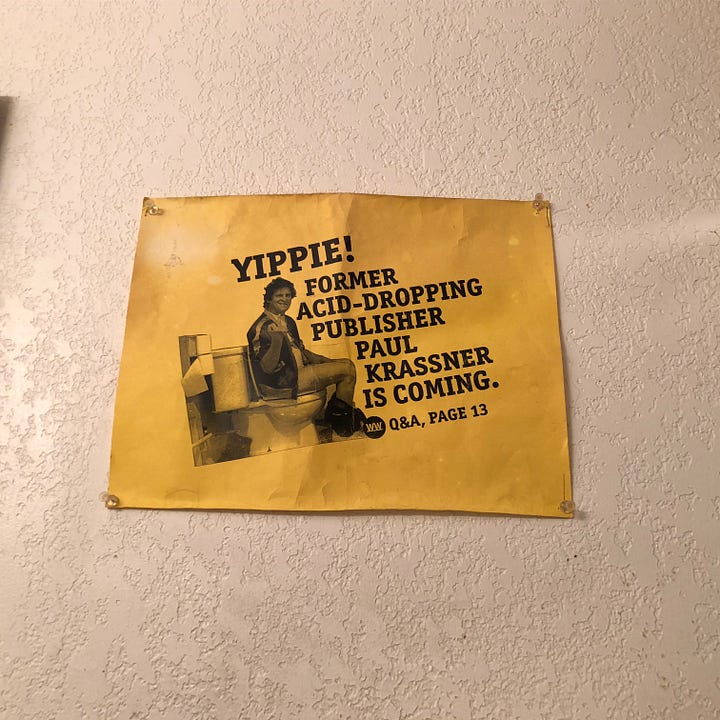

Paul Krassner on Lenny Bruce, Old Times Police Brutality, & Cavalier Magazine - Ya Gotta Love Him

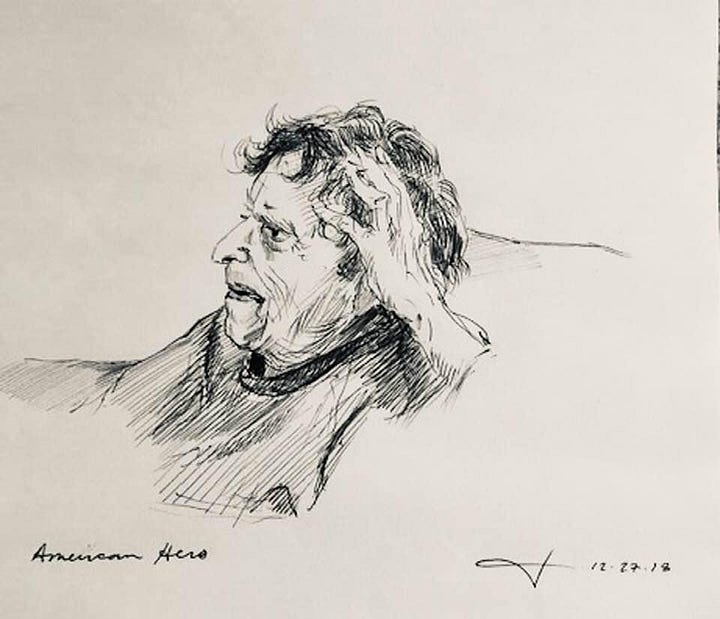

You know who I miss extra, extra much?

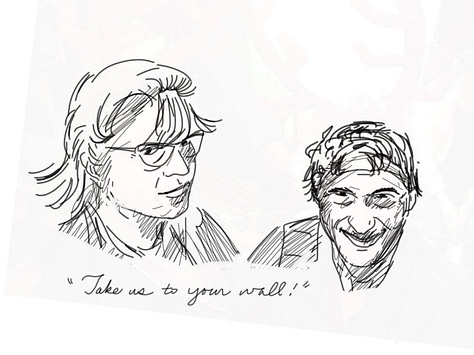

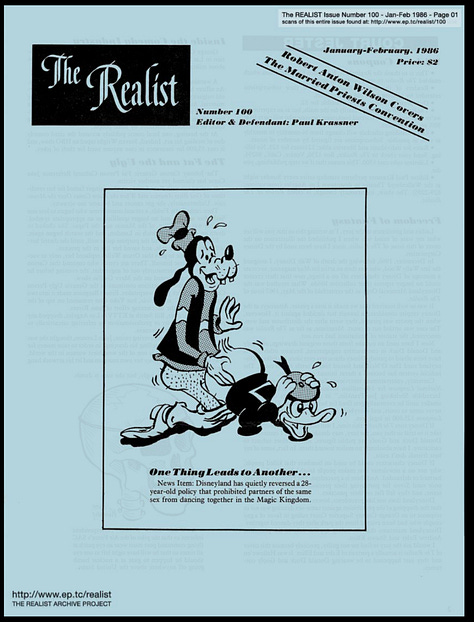

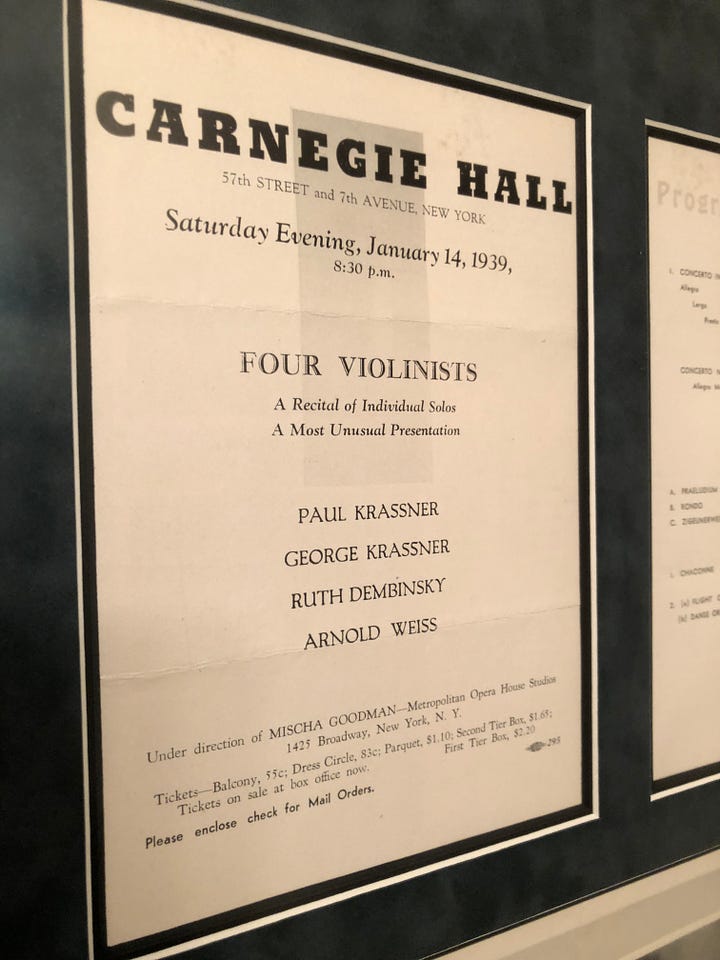

My friend Paul Krassner. Revolutionary Prankster about town. He was bohemian spirit of the 1960s, the very best of it. The editor of The Realist.

—A wit like no one else, and warmth like a hug you’d never let go. He’s been gone six years now.