Motherhood - The Early Days When I Knew Everything

I got pregnant in 1989, when I was 32

I got pregnant in 1989, when I was 32, the same age as my mother when she had me. I was due in early June, which inspired a flood of Gemini well-wishes from the On Our Backs readers, who were as surprised and curious as everyone else.

“Did you inseminate or did you party?” asked Marika at our magazine Xmas Party.

I laughed so hard, she said, “Oh! You partied.”

I did party. But I also was falling in love. And then out of it. My bisexual heart was in a bit of torment.

It was the eve of a baby boom— I didn’t know any other women my age who were taking the plunge. They’d either done it a lot earlier, or had foresworn the whole racket— the latter included me.

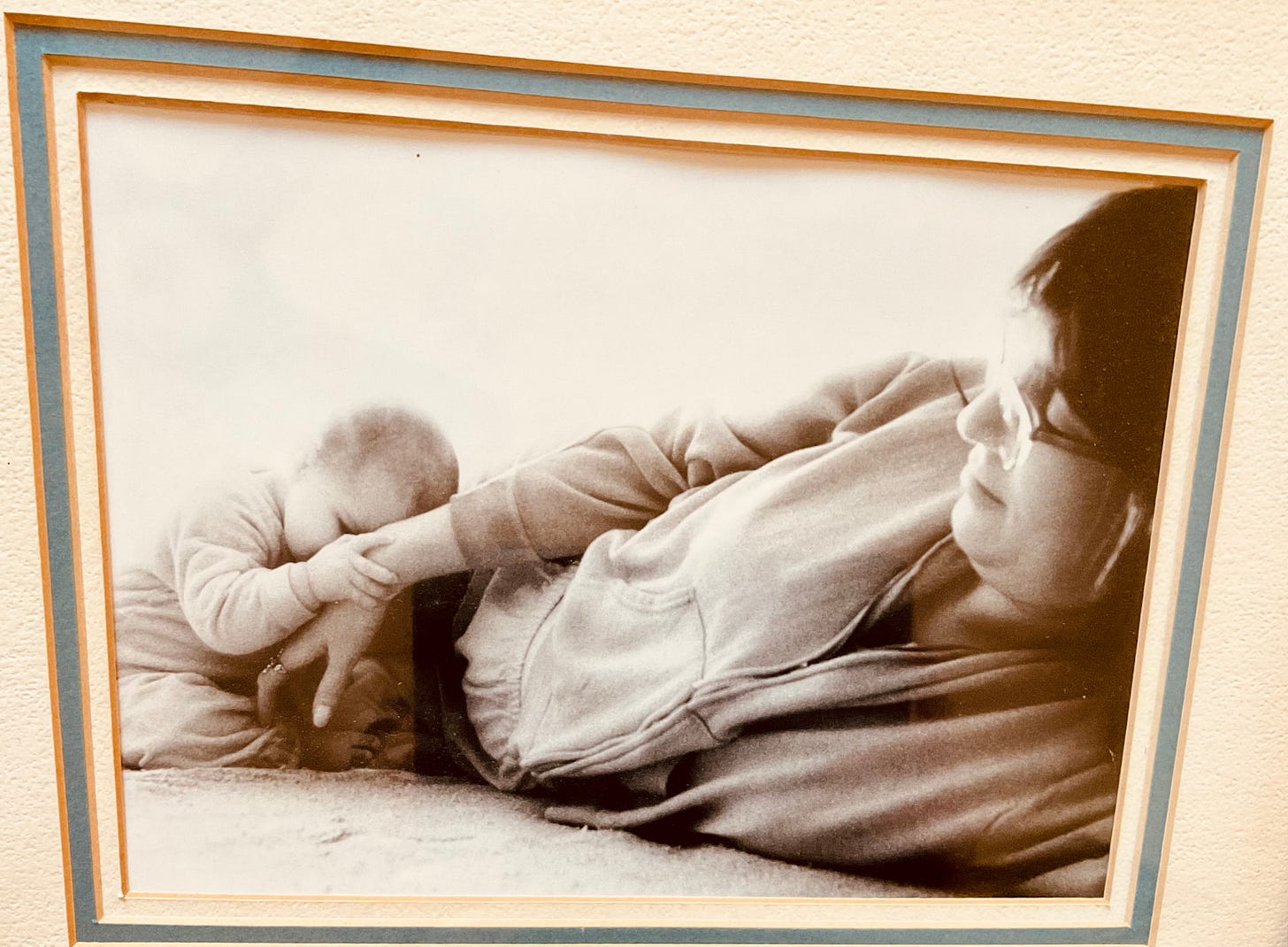

My daughter-to-be, Aretha Elizabeth Bright, surprised me in every way— including her late-June Cancerian arrival. She had eyes like dark moons and when the midwife put her in my arms she looked into me, like no one has ever looked at me before.

When Aretha was six months old, an old neighbor of mine…