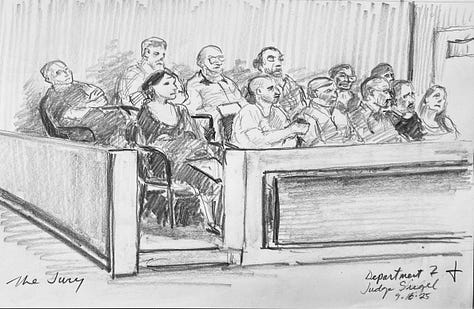

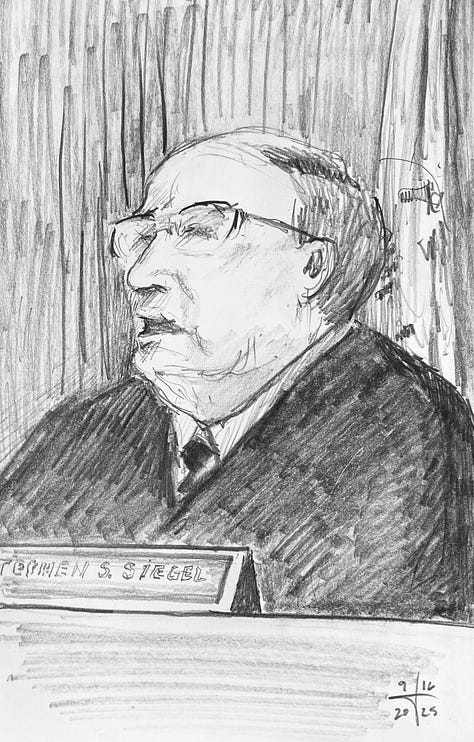

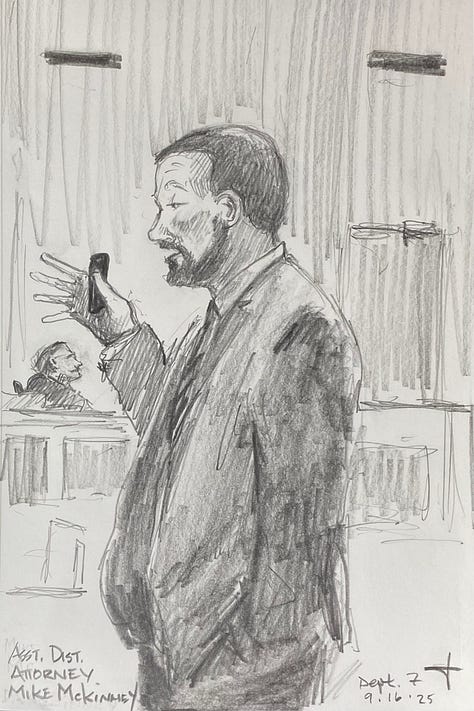

In the Courtroom— Everything on the Line

What it looked like 56 years ago, what it looks like today

Last week I attended a murder trial. —a tragedy, as you may guess.

I’m not connected to any of the principals— I’m an observer. I felt like a quiet eye, the recorder.

I’m not writing today about the crime in question— another time, as things conclude.

Today, it’s something else.

Do you know what struck me in the trial? —Not the particulars of the case.

Rather, it was the way in which the courtroom, and everyone in it, behaved with immaculate decorum.

No one interrupted anyone else. When the attorneys gave their summations, all eyes were upon them, silent. There were scheduled breaks for all to take a breather, and then the serious work resumed. About 50 people were in that courtroom, all doing their jobs and their best.

Pinch me.