I have a recurring nightmare my mother is alive

Bringing Up the Dead

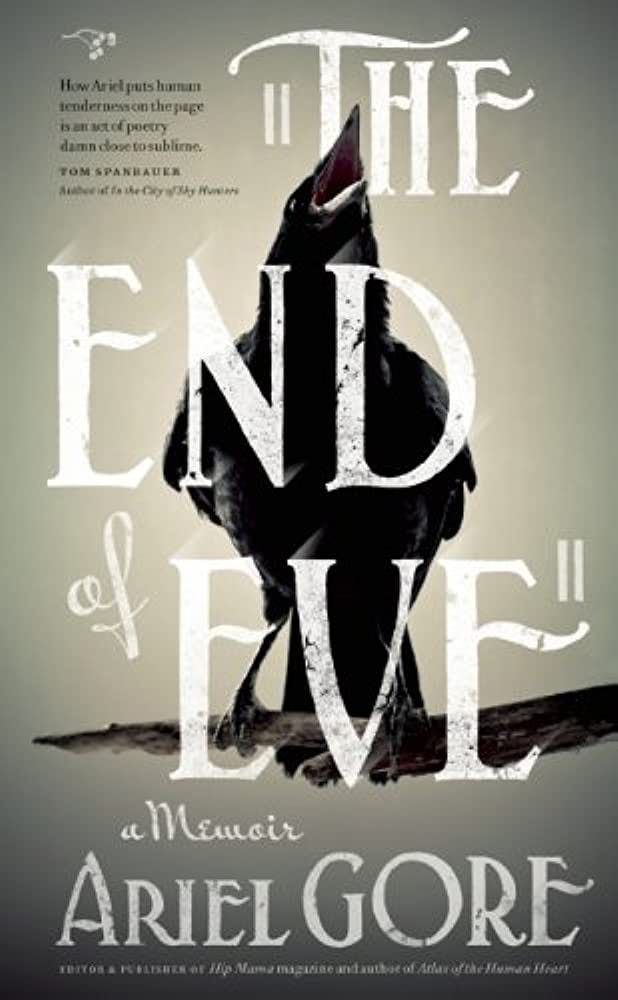

By Ariel Gore

She never died.

I've made a terrible mistake.

I have to call my editor.

“We can't publish the book.”

I don't know how I could have made such a wild mistake.

I mean, she looked dead.

I signed the papers. I let the man from the cut-rate crematorium in Albuquerque take her body away.

But in the dream, she isn't dead.

And in the dream, she's really pissed about the book. It’s all about her.

I can't get through to my editor. Of course I can't get through. It's too late. It's already out, anyway. My editor can't do anything.

Maybe I can hide the books.

Or.

Maybe.

Just walk away.

I'd been having the dream for nearly six months the night it occurred to me: it didn't matter if she was alive.

If I'd lived these many months believing she was dead, feeling freer because she was dead, writing the truth without worrying about cleaning it up because she was dead, then who cared if she was alive — or pissed?